Isolated as we are by national lockdowns and statewide stay-at-home orders, many coworkers are more connected than ever before through oddly-named productivity/chat programs such as Slack. But those notifications flying in from the sidebar all the time are are oh-so-annoying and anti-productive. Ignoring requests for your attention will only make them multiply. So how do you make the notifications bearable?

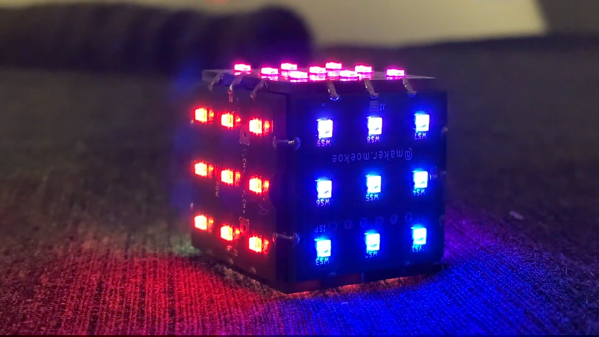

[Mr. Tom] wrote in to tell us about his solution, which involves a maneki-neko — one of those good luck cats that wave slowly and constantly thanks to a solar-powered electromagnetic pendulum. Now whenever [Mr. Tom] has an incoming message, the cat starts waving gently over on the corner of his desk. It’s enough movement to be noticeable, but not annoying.

An ESP32 inside the kitty looks at incoming messages and watches for [Mr. Tom]’s user ID, prioritizing messages where he has been mentioned directly. This kitty is smart, too. As soon as the message is dealt with, the data pin goes low again, and the cat can take a nap for a while.

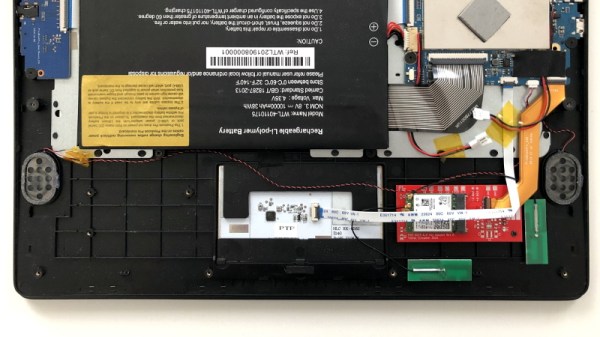

The natural state of the maneki-neko is pretty interesting, as we saw in this teardown a few years back.