Contactless payments are growing in popularity. Often the term will bring to mind the ability to pay by holding your phone over a reader, but the system can also use NFC tags embedded in credit cards, ID card, passports, and the like. NFC is a reasonably secure method of validating payments as it employs encryption and the functional distance between client and reader is in the tens of centimeters, and often much less. [Haoqi Shan] and the Unicorn team have reduced the security of the distance component by using a hardware proxy to relay NFC interactions over longer distances.

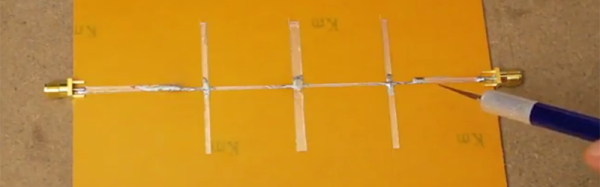

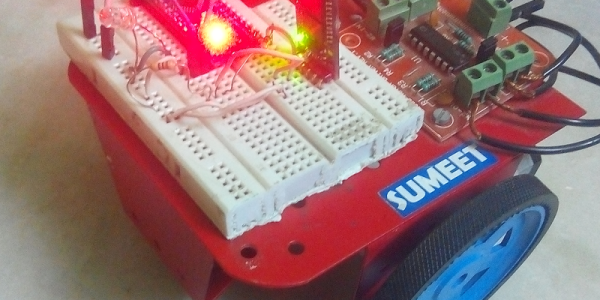

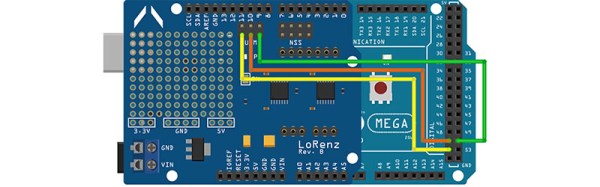

The talk, give on Sunday at DEF CON, outlined some incredibly simple hardware: an NFC antenna connected to a PN7462AU, an NRF24L01 wireless transceiver, and some power regulation. The exploit works by using a pair of these hardware modules. A master interfaces with the NFC reader, and a slave reads the card. The scenario goes something like this: a victim NFC card is placed near the slave hardware. The master hardware is placed over a payment kiosk as if making a normal payment. As the payment kiosk reader begins the process to read an NFC card, all of the communications between it and the actual card are forwarded over the 24L01 wireless connection.

The demo video during the talk showed a fast-food purchase made on the Apple Pay network while the card was still at a table out in the dining area (resting on the slave hardware module). The card used was a QuickPass contactless payment card from China UnionPay. According to a 2016 press release from the company, over two billion of these cards had been issued at the time. With that kind of adoption rate there is a huge incentive to find and patch any vulnerabilities in the system.

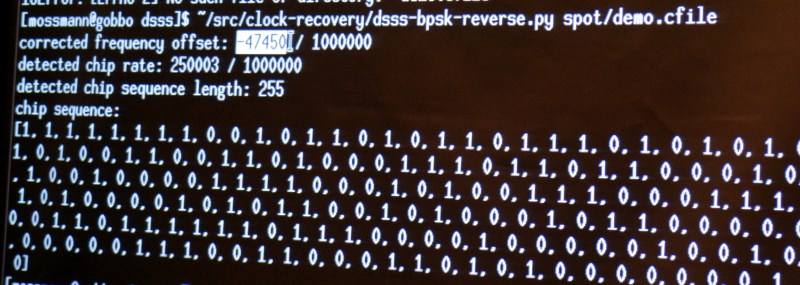

The hardware components in this build aren’t really anything special. We’ve seen these Nordic wireless modules used in numerous projects over they years, and the NXP chip is just NFC build around an ARM core. The leaps that tie this together are the speed-ups to make it work. NFC has tight timing and a delay between the master and slave would invalidate the handshake and subsequent interactions. The Unicorn team found some speedups by ensuring the chip was waking from suspend mode (150 µS) and not a deeper sleep. Furthermore, [Haoqi] mentioned they are only transmitting “I/S/R Block Data” and not the entirety of the interaction to save on time transmitting over the 24L01 wireless link. He didn’t expand on that so if you have details about what those blocks actually consist of please let us know in the comments below.

To the card reader, the emulated payment card is valid and the payment goes through. But one caveat to the system is that [Haoqi] was unable to alter the UID of the emulator — it doesn’t spoof the UID of the payment card being exploited. Current readers don’t check the UID and this could be one possible defense against this exploit. But to be honest, since you need close physical proximity of the master to the reader and the slave to the payment card simultaneously, we don’t see mayhem in the future. It’s more likely that we’ll see hacker cred when someone builds a long-range link that lets you leave your NFC cards at home and take one emulator with you for wireless door access or contactless payments in a single device. If you want to get working on this, check out the talk slides for program flow and some sourcecode hints.

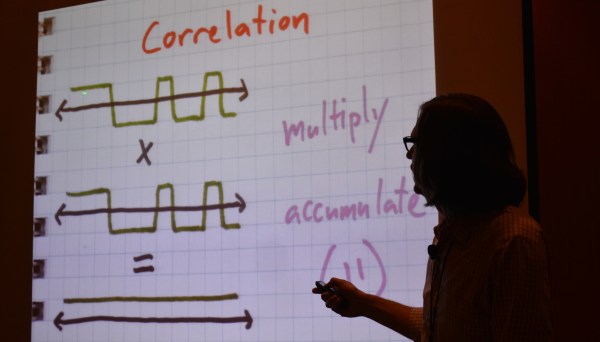

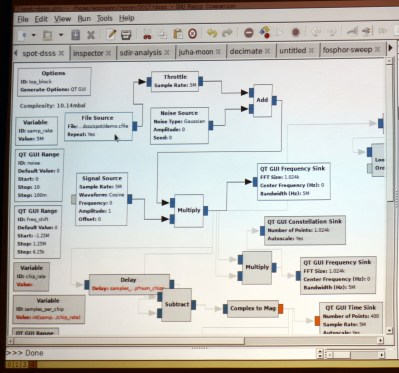

[Michael] mentioned simple math tricks, and he wasn’t kidding. It’s easy to assume that someone as experienced in RF as he would have a different definition of ‘simple’ than we would. But truly, he’s using multiplication and subtraction to do an awful lot.

[Michael] mentioned simple math tricks, and he wasn’t kidding. It’s easy to assume that someone as experienced in RF as he would have a different definition of ‘simple’ than we would. But truly, he’s using multiplication and subtraction to do an awful lot.