When debugging ordinary low-voltage circuitry, you’re pretty safe: unless you have some really power-hungry devices that need a ton of current, there aren’t that many truly bad things that can happen, so you can take a lot of liberties with electrical-safety rules. With mains-powered devices, you don’t have this luxury, and a lack of knowledge, sloppy work practices, or simple mistakes can cost you — and your project — dearly. While you still need to know what you’re doing and use the requisite caution, [Yann Guidon]’s latest project — and entry in the 2019 Hackaday Prize — a mains protection box, might keep simple mistakes from becoming a disaster.

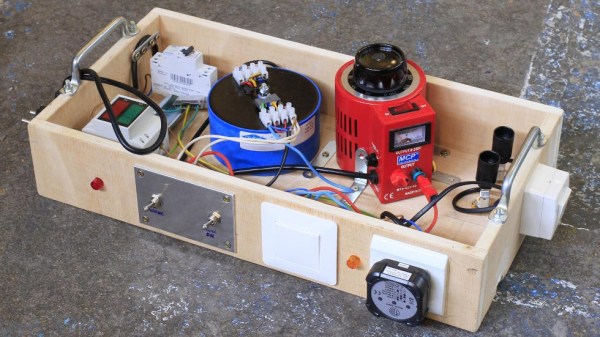

There are a number of precautions you can take when working with mains power. We’ve all used the simple in-line power strip so you can quickly switch off the current, but [Yann] has included a number of devices that can be configured in different ways to experiment with mains-powered devices safely. Built into a sturdy open-topped wooden box with carry handles, the project evokes the traditional breadboard in appearance and functionality. A number of different devices are included, which could be re-configured into different topologies if needed.

[Yann] included an isolation transformer, which can be useful not only for protection against shock in case of accidentally grounding, but also for noise suppression. There is also a variac, which allows the output voltage to be adjusted over a wide range for testing. Of course, circuit breakers are a must, and current and voltage meters keep you informed about what’s going on. A big, easy-to-access switch cuts the power quickly when needed.

The (maybe) final touch is an adjustable output current limit, which is still a work in progress. Built around a current-monitoring relay and a DPDT relay wired as a latch, this allows the output to be disconnected if it draws more than a specified current, equivalent to between 10 W and 100 W. This is the perfect thing for initial testing of new projects.

So, if you’re thinking of working on mains-powered projects, have a close look at what [Yann] has assembled, and learn proper safety procedures before you begin. One place to start is with a great series by our own Jenny List about mains safety: part one and part two. Stay safe out there!