[MostElectronics], like many of us, loves cats, and so wanted to make an internet connected treat dispenser for their most beloved. The result is an ingenious 3D printed mechanism connected to a Raspberry Pi that’s able to serve treats through a locally run web application.

From the software side, the Raspberry Pi uses a RESTful API that one can connect to through a static IP. The API is implemented as a Python Flask application running under a stand alone web server Python script. The web application itself keeps track of the number of treats left and provides a simple interface to dispense treats at the operators leisure. The RpiMotorLib Python library is used to control a 28BYJ-48 stepper motor through its ULN2003 controller module, which is used to rotate the inside shaft of the treat dispenser.

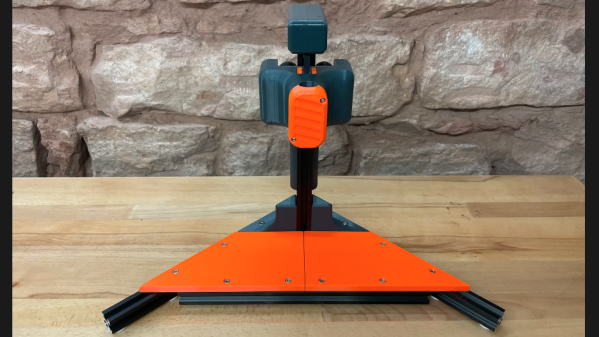

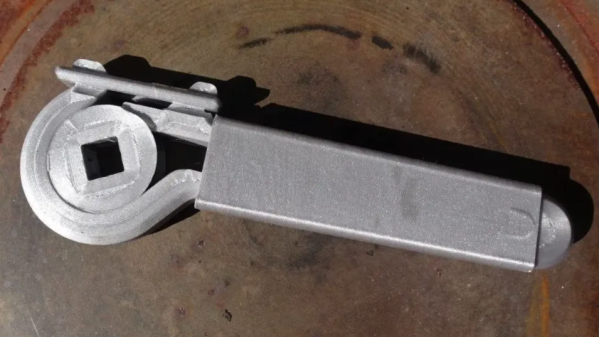

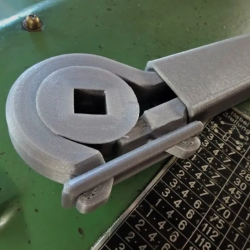

The mechanism to dispense treats is a stacked, compartmentalized drum, with two drum layers for food compartments that turn to drop treats. The bottom drum dispenses treats through a chute connected to the tray for the cat, leaving an empty compartment that the top drum can replenish by dropping its treats into through a staggered opening. Each compartmentalized treat drum layer provides 11 treats, allowing for a total of 22 treats with two layers stacked on top of each other. One could imagine extending the treat dispenser to include more drum layers by adding even more layers.

Source code is available on GitHub and the STL files for the dispenser are available on Thingiverse. We’ve seen cat electronic feeders before, sometimes with escalating consequences that shake us to our core and leave us questioning our superiority.

Video after the break!