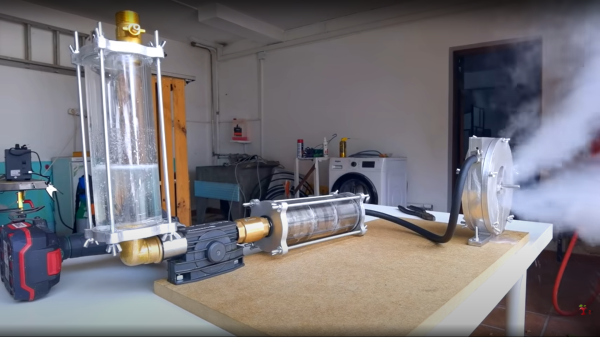

If you’re out in the wilderness and off the grid, but still need to charge your phone, the most obvious way to do that is by using a solar panel. Light, flat and without moving parts, they’re easy to store and carry on a hike. But they obviously don’t work in the dark, so what’s a hiker to do if they want to charge their devices at night? If you happen to be in a windy place, then [adriancubas] has the solution for you: a portable wind turbine that folds up to the size of a 2 L soda bottle.

[adrian] designed the turbine to be light and compact enough to take with him on multi-day camping trips. Nearly all parts are 3D printed in PLA, and although ABS or PETG would have been stronger, the current design seems to hold up well in a moderate breeze. The generator core is made from a stepper motor with a bridge rectifier and a capacitor to create a DC output. [adrian] estimates the maximum power output to be around 12 W, which should be more than enough to charge a few beefy power banks overnight.

All parts are available as STL files on [adrian]’s project page, so if you’re looking for some wind power to charge your gadgets on your next camping trip you can go ahead and build one yourself. While we’ve seen large 3D printed wind turbines before, and portable ones for hikers, [adrian]’s clever folding design is a neat step up towards making wind power almost as easy to use as solar power.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize 2022: A 3D Printed Portable Wind Turbine For Hikers”

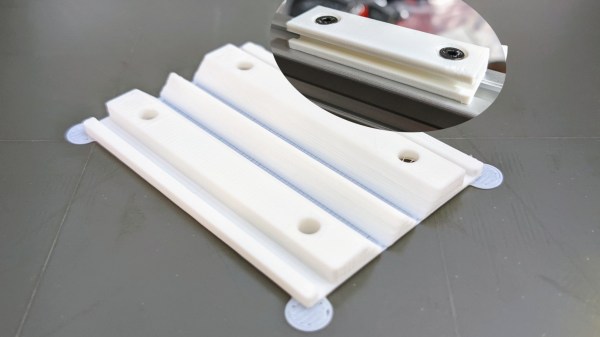

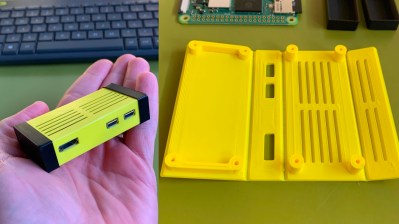

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable

The example Chris provides is a Eurorack rail segment — due to the kind of overhangs required, you’d be inclined to print it vertically, taking a hit to the print time and introducing structural weaknesses. With this trick, you absolutely don’t have to! You can also go way further and 3D print a single-piece foldable