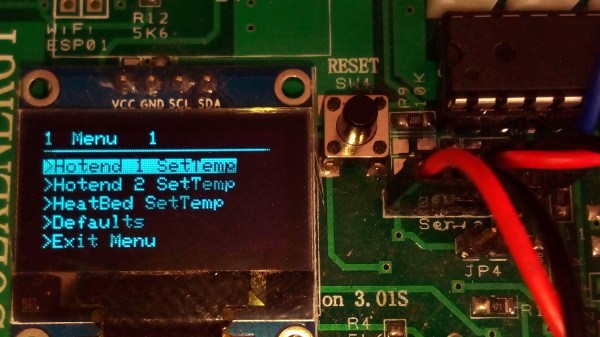

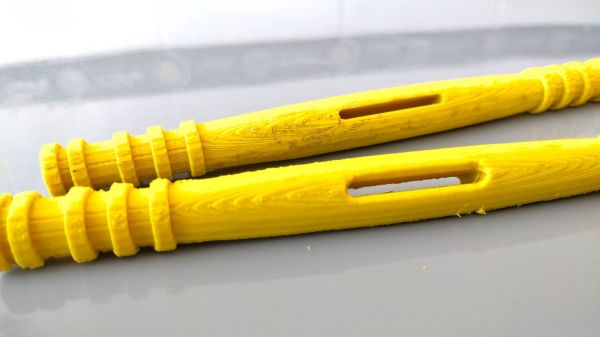

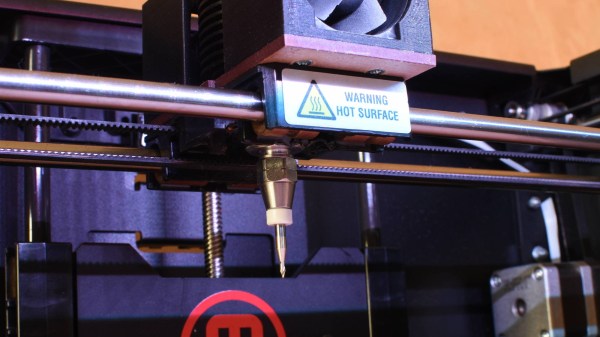

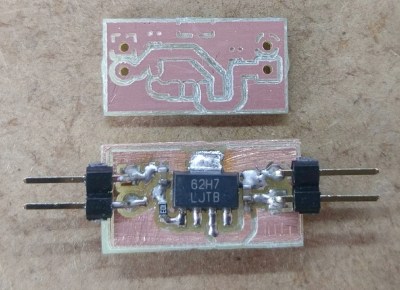

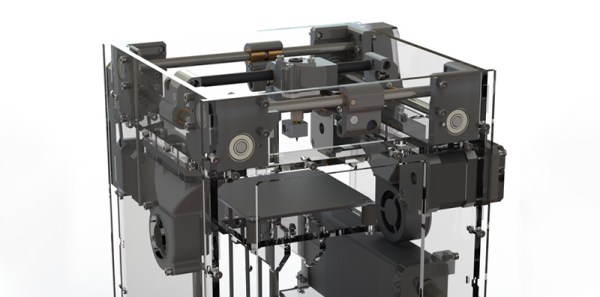

Some devices have one job to do, but that job can have many facets. To [jmcservv], an example of this is the job of protecting against worst-case failures in a 3D printer, and it led him to develop the 3D Printer Watchdog Guardian. When it comes to fire, secondary protection is the name of the game because it’s one thing to detect thermal runaway and turn off a heater, but what if that isn’t enough? The MOSFET controlling the heater could have failed closed and can no longer be turned off in a normal sense. In such cases, some kind of backup is needed. Of course, a protection system should also notify an operator of any serious problem, but what’s the best way to do that? These are the kinds of issues that [jmcservv] is working to address with his watchdog, which not only keeps a careful eye on any heating elements in the system, but can take a variety of actions as a result.

Some outcomes (like fire) are bad enough that it’s worth the extra work and cost of additional protection, and that’s the thinking that has led [jmcservv] to submit his watchdog system for The Hackaday Prize.