The Altoids tin has long been the enclosure of choice for those seeking to show off their miniaturization chops. This is especially true for amateur radio homebrewers — you really have to know what you’re doing to stuff a complete radio in a tiny tin. But when you can build an entire 80-meter transceiver in a matchbox, that’s a whole other level of DIY prowess.

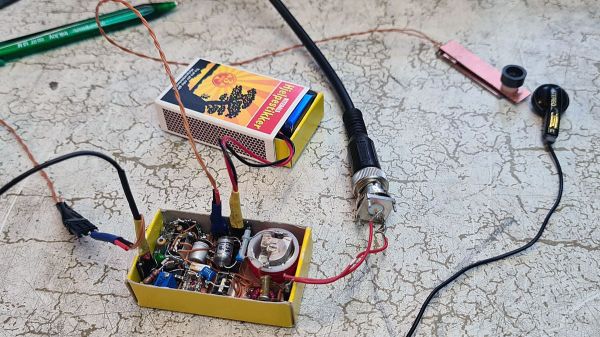

It’s no surprise that this one comes to us from [Helge Fykse (LA6NCA)], who has used the aforementioned Altoids tin to build an impressive range of “spy radios” in both vacuum tube and solid-state versions. He wisely chose solid-state for the matchbox version of the transceiver, using just three transistors and a dual op-amp in a DIP-8 package. There’s also an RF mixer in an SMD package; [Helge] doesn’t specify the parts, but it looks like it might be from Mini-Circuits. Everything is mounted dead bug style on tiny pieces of copper-clad board that get soldered to a board just the right size to fit in a matchbox.

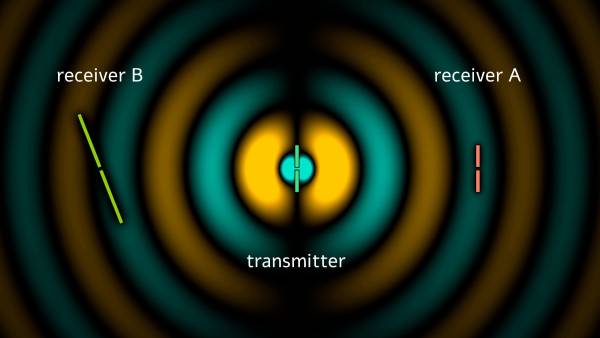

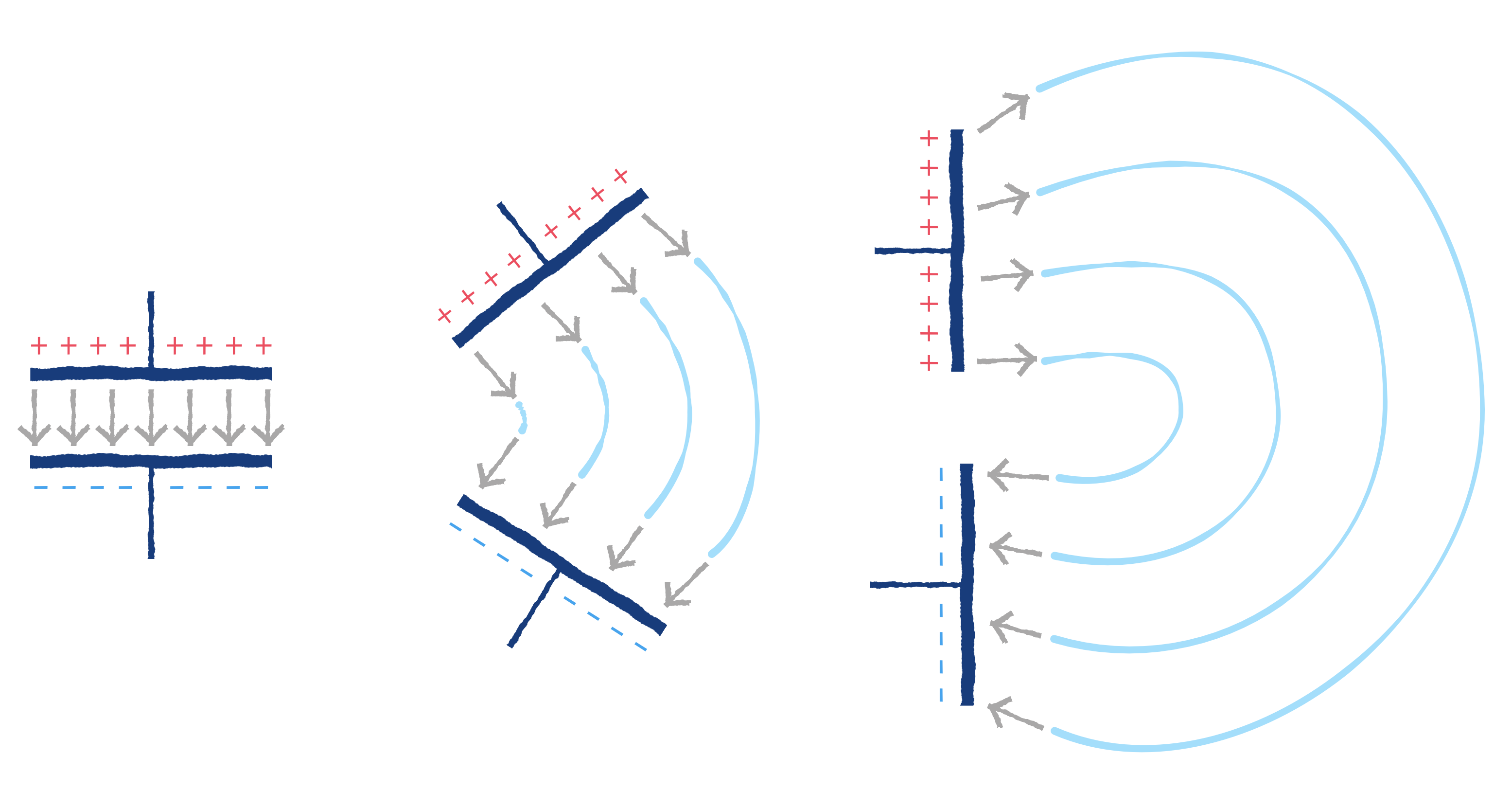

A 9 volt battery, riding in a separate matchbox, powers the rig. As do the earbud and tiny Morse key. That doesn’t detract from the build at all, and neither does the fact that the half-wave dipole antenna is disguised as a roll of fishing line. [Helge]’s demo of the radio is impressive too. The antenna is set up very low to the ground to take advantage of near vertical incidence skywave (NVIS) propagation, which tends to direct signals straight up into the ionosphere and scatter them almost directly back down. This allows for medium-range contacts like [Helge]’s 239 km contact in the video below.

Banging out Morse with no sidetone was a challenge, but it’s a small price to pay for such a cool build. We’re not sure how much smaller [Helge] can go, but we’re eager to see him try.

Continue reading “Matchbox Transceiver Pushes The Spy Radio Concept To Its Limits”