[Buttim] loses his car a lot, which might sound a little bit like the plot from an early-00s movie, but he assures us that it’s a common enough thing. In a big city, and after several days of not driving one’s car, it can be possible to at least forget where you parked. There are a lot of ways of solving this problem, but the solution almost fell right into his lap: repurposing a lock from a bike share bicycle. (The build is in three parts: Part 2 and Part 3.)

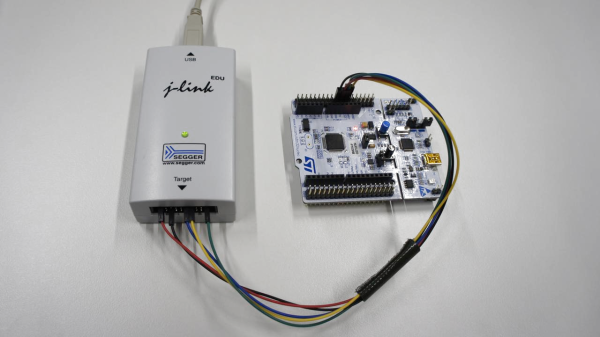

These locks are loaded with features, like GPS, a cellular modem, accelerometers, and in this case, an ARM processor. It took a huge amount of work for [Buttim] to get anything to work on the device, but after using a vulnerability to dump the firmware and load his own code on the device, spending an enormous amount of time trying to figure out where all the circuit traces went through layers of insulation intended to harden the lock from humidity, and building his own Python-based programmer for it, he has basically free reign over the device.

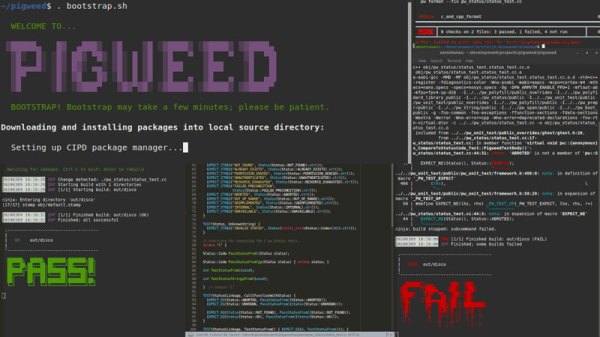

To that end, once he figured out how it all worked, he put it to use in his car. The device functions as a GPS tracker and reports its location over the cellular network so it can’t become lost again. As a bonus, he was able to use the accelerometers to alert him if his car was moving without him knowing, so it turned into a theft deterrent as well. Besides that, though, his ability to get into the device’s firmware reminded us of a recent attempt to get access to an ARM platform.

Google

Google