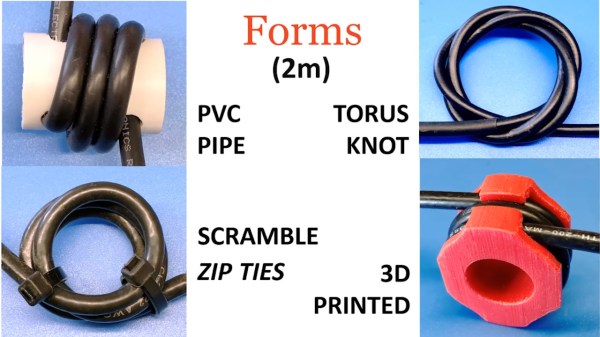

Even before entering the mystical realms of UHF design, radio frequency (RF) circuits come with a whole range of fun design aspects as well. A case in point can be found in transmission line transformers, which are commonly used in RF power amplifiers, with the Guanella transformer (balun) being one example. Allowing balanced and unbalanced (hence ‘balun’) systems to interface without issues, they’re both very simple and very complex. This type of transformer and its various uses is explained in a video by [FesZ Electronics], and also the subject of an article by [Dr. Steve Arar] as part of a larger series, the latter of which is recommended to start with you’re not familiar with RF circuitry.

Transmission line transformers are similar to regular transformers, except that the former relies on transmission line action to transfer energy rather than magnetic flux and provides no DC isolation. The Guanella balun transformer was originally described by Gustav Guanella in 1944. Beyond the 1:1 balun other configurations are also possible, which [Dr. Arar] describes in a follow-up article, and which are also covered in the [FesZ] video, alongside the explanation of another use of Guanella transformers: as an impedance transformer. This shows just how flexible transformers are once you can wrap your mind around the theory.

We have previously covered RF amplifier builds as well as some rather interesting balun hacks.

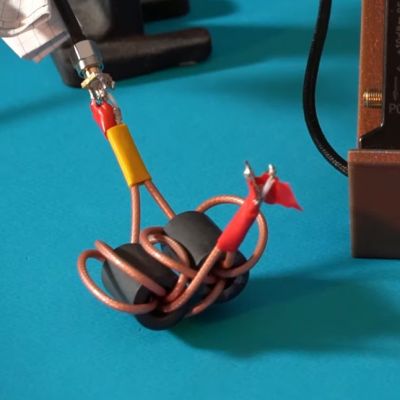

Heading image: The Guanella 1:1 balun. (Credit: Steve Arar)

Continue reading “Using Guanella Baluns As Impedance Transformers”

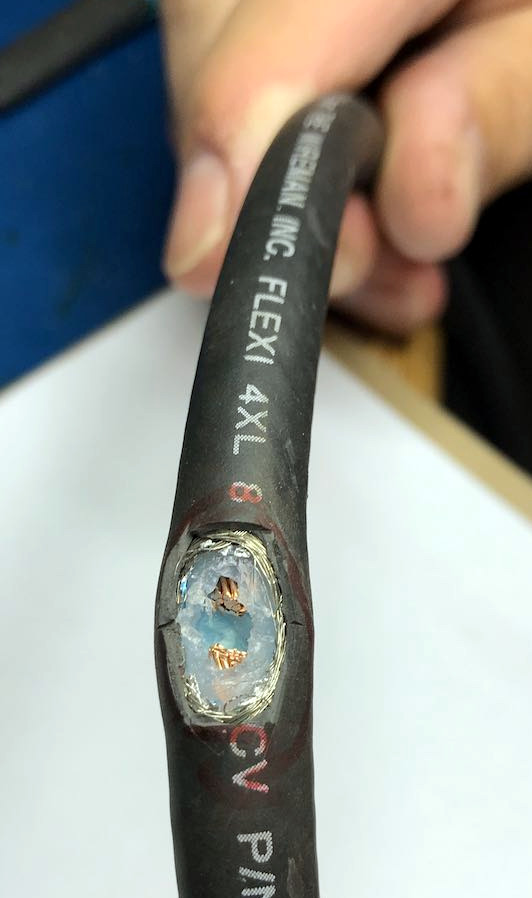

To be honest, pretty much any chunk of wire will do as an antenna for most shortwave receivers. But not everyone lives somewhere where it’s possible to string up a hundred meters of wire and get a good ground connection, which could make a passive loop antenna like this a good choice. Plus, loops tend to cancel the electrical noise that’s so part of life today, which can make it easier to pull in weak, distant stations.

To be honest, pretty much any chunk of wire will do as an antenna for most shortwave receivers. But not everyone lives somewhere where it’s possible to string up a hundred meters of wire and get a good ground connection, which could make a passive loop antenna like this a good choice. Plus, loops tend to cancel the electrical noise that’s so part of life today, which can make it easier to pull in weak, distant stations.