The demand for grid storage ramps up as more renewable energy sources comes online, but existing technology might not be up to the challenge. Lithium is the most popular option for battery storage right now, not just due to the physical properties of the batteries, but also because we’re manufacturing them at a massive scale already. Unfortunately they do have downsides, especially with performance in cold temperatures and a risk of fires, which has researchers looking for alternatives like aqueous batteries which mitigate these issues.

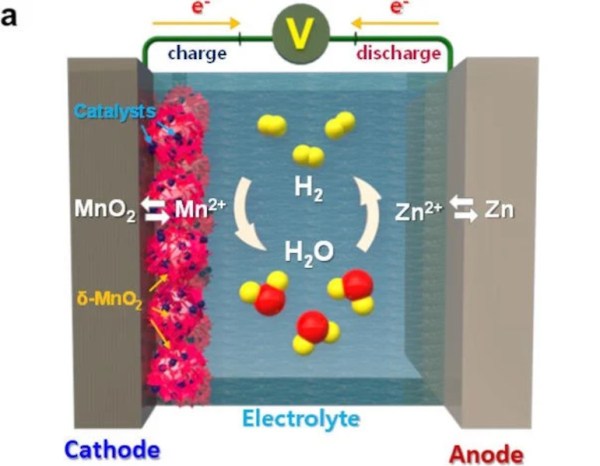

An aqueous battery uses a water-based electrolyte to move ions from one electrode to the other. Compared to lithium, which uses lithium salts for the electrolyte, this reduces energy density somewhat but improves safety since water is much less flammable. The one downside is that during overcharging or over-current situations, hydrogen gas can be produced by electrolysis of the water, which generally needs to be vented out of the battery. This doesn’t necessarily damage the battery but can cause other issues. To avoid this problem, researchers found that adding a manganese oxide to the battery and using palladium as a catalyst caused any hydrogen generated within the battery’s electrolyte to turn back into water and return to the electrolyte solution without issue.

Of course, these batteries likely won’t completely replace lithium ion batteries especially in things like EVs due to their lower energy density. It’s also not yet clear whether this technology, like others we’ve featured, will scale up enough to be used for large-scale applications either, but any solution that solves some of the problems of lithium, like the environmental cost or safety issues, while adding more storage to an increasingly renewable grid, is always welcome.