With the never ending march of technological progress, arguably the most complex technologies become so close to magic as to be impenetrable to those outside the industry in which they operate. We’ve seen walkthrough video snapshots of just a small part of the operation of modern semiconductor fabs, but let’s face it, everything you see is pretty guarded, hidden away inside large sealed boxes for environmental control reasons, among others, and it’s hard to really see what’s going on inside.

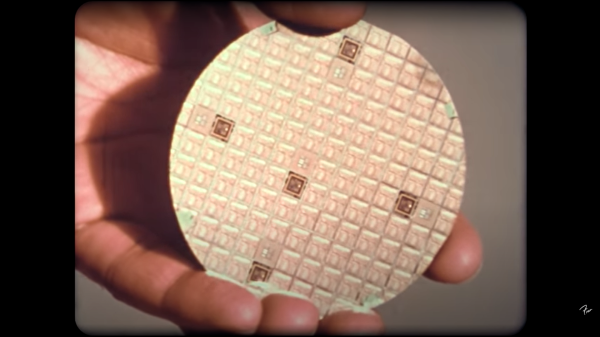

Let’s step back in time a few decades to 1983, with an interesting tour of the IC manufacturing facility at Bell Labs at Murray Hill (video, embedded below) and you can get a bit more of an idea of how the process works, albeit at a time when chips hosted mere tens of thousands of active devices, compared with the countless billions of today. This fab operates on three inch wafers, producing about 100 die each, with every one handled and processed by hand whereas modern wafers are much bigger, die often much smaller with the total die per wafer in the thousands and are never handled by a filthy human.

Particle counts of 100 per cubic foot might seem laughable by modern standards, but device geometries back then were comparatively large and the defect rate due to it was not so serious. We did chuckle somewhat seeing the operator staff all climb into their protective over suits, but open-faced with beards-a-plenty poking out into the breeze. Quite simply, full-on bunny suits were simply not necessary. Anyway, whilst the over suits were mostly for the environment, we did spot the occasional shot of an operator wearing some proper protective face shielding when performing some of the higher risk tasks, such as wafer cleaning, after all as the narrator says “these acids are strong enough to eat through the skin” and that would certainly ruin your afternoon.

No story about integrated circuit processing would be complete without mentioning the progress of [Sam Zeloof] and his DIY approach to making chips, and whilst he’s only managing device counts in the hundreds, this can only improve given time.

Continue reading “Integrated Circuit Manufacturing At Bell Labs In 1983” →