The earliest useful plastics were made out of natural materials like cellulose and casein, but since the Bakelite revolution, their use has dwindled away and left them mostly as curiosities and children’s science experiments. Fortunately, though, the raw materials for bioplastics are readily available in most grocery stores, and as [Ben] from NightHawkInLight demonstrates, it’s still possible to find new uses for them.

His first recipe was for a clear gelatine thermoplastic, using honey as a plasticizer, which he formed into the clear packet around some instant noodles: simply throw the whole packet into hot water, and the plastic dissolves away. With some help from the home bioplastics investigator [Giestas], [Ben] next created a starch-based plastic out of starch, vinegar, and glycerine. Starch is a good infrared emitter in the atmospheric window, and researchers have made a starch-plastic aerogel that radiates enough heat to become cooler than its surroundings. Unfortunately, this requires freeze-drying, and while encouraging freezer burn in a normal freezer can have the same effect, it’ll take a few months to get a usable quantity of the material.

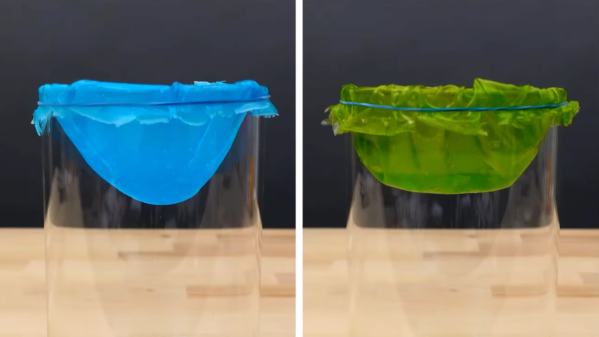

The other problem with starch-based plastics is their tendency to absorb water, at least when paired with plasticizers like glycerine or honey. Bioplastics based on alginate, however, are easy to make waterproof. A solution of sodium alginate, derived from seaweed, reacts with calcium ions to make a cross-linked waterproof film. Unfortunately, the film forms so quickly that it separates the solutions of calcium ions from the alginate, and the reaction stops. To get around this, [Ben] mixed a sodium alginate solution with powdered calcium carbonate, which is insoluble and therefore won’t react. To make the plastic set, he added glucono delta lactone, which slowly breaks down in water to release gluconic acid, which dissolves the calcium carbonate and lets the reaction proceed.

The soluble noodle package reminded us of a similar edible package, which included flavoring in the plastic. We’ve also seen alginate used to make conductive string, and rice used to make 3D printer filament. It’s worth some caution, though – not all biologically-derived plastics are healthier than synthetic materials.