[Jiska Classen] and [Dennis Mantz] created a tool called Internal Blue that aims to be a Swiss-army knife for playing around with Bluetooth at a lower level. The ground for their tool is based in three functions that are common to all Broadcom Bluetooth chipsets: one that lets you read arbitrary memory, on that lets you run it, and one that lets you write it. Well, that was easy. The rest of their work was analyzing this code, and learning how to replace the firmware with their own version. That took them a few months of hard reversing work.

In the end, Internal Blue lets them execute commands at one layer deeper — the LMP layer — easily allowing monitoring and injection. In a series of live (and successful!) demos they probe around on a Nexus 6P from a modified Nexus 5 on their desk. This is where they started digging around in the Bluetooth stack of other devices with Broadcom chipsets, and that’s where they started finding bugs.

As is often the case, [Jiska] was just poking around and found an external code handler that didn’t do bounds checking. And that meant that she could run other functions in the firmware simply by passing the

As is often the case, [Jiska] was just poking around and found an external code handler that didn’t do bounds checking. And that meant that she could run other functions in the firmware simply by passing the address handler offset. Since they’re essentially calling functions at any location in memory, finding which functions to call with which arguments is a process of trial and error, but the ramifications of this include at least a Bluetooth module crash and reset, but can also pull such tricks as putting the Bluetooth module into “Device Under Test” mode, which should only be accessible from the device itself. All of this is before pairing with the device — just walking by is sufficient to invoke functions through the buggy handler.

All the details of this exploit aren’t yet available, because Broadcom hasn’t fixed the firmware for probably millions of devices in the wild. And one of the reasons that they haven’t fixed it is that patching the bug will disclose where the flaw lies in all of the unpatched phones, and not all vendors can be counted on to push out updates at the same time. While they focused on the Nexus 5 cellphone, which is fairly old now, it’s applicable to any device with a similar Broadcom Bluetooth chipset.

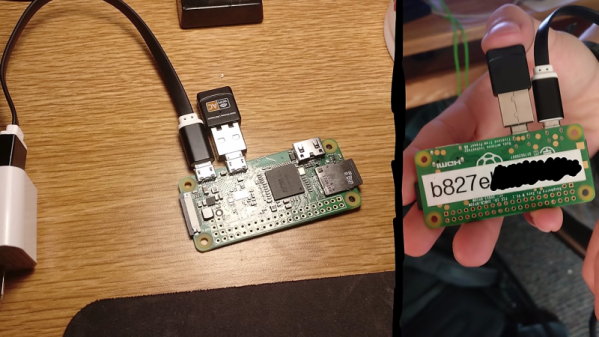

Aside from the zero-day bug here, the big story is their Bluetooth analysis framework which will surely help other researchers learn more about Bluetooth, finding more glitches and hopefully helping make Bluetooth more openly scrutinized and more secure. Now anyone with a Raspberry Pi 3/3+ or a Nexus 5, is able to turn it into a low-level Bluetooth investigation tool.

You might know [Jiska] from her previous FitBit hack. If not, be sure to check it out.

Continue reading “35C3: Finding Bugs In Bluetooth” →

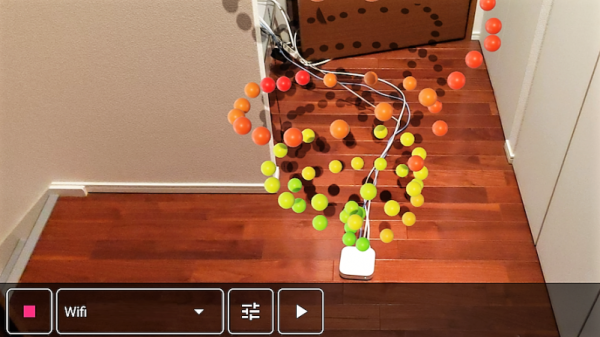

Unwilling to go full [Geordi La Forge] to be able to visualize RF, [Ken Kawamoto] built the next best thing –

Unwilling to go full [Geordi La Forge] to be able to visualize RF, [Ken Kawamoto] built the next best thing –