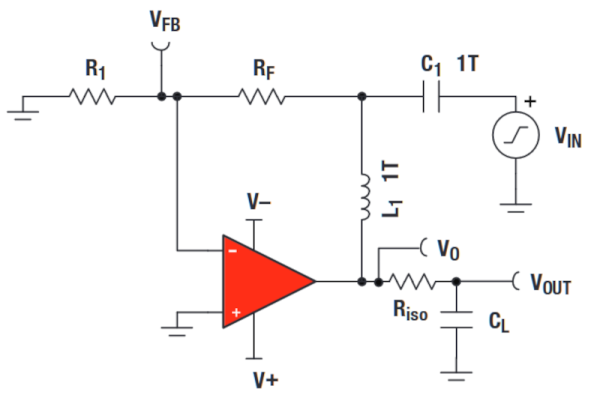

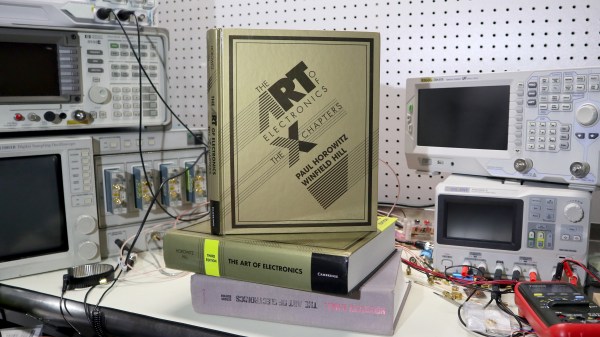

If you’ve been into electronics for any length of time, you’ve almost certainly run across the practical bible in the field, The Art of Electronics, commonly abbreviated AoE. Any fan of the book will certainly want to consider obtaining the latest release, The Art of Electronics: The x-Chapters, which follows the previous third edition of AoE from 2015. This new book features expanded coverage of topics from the previous editions, plus discussions of some interesting but rarely traveled areas of electrical engineering.

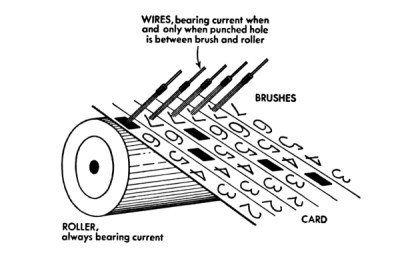

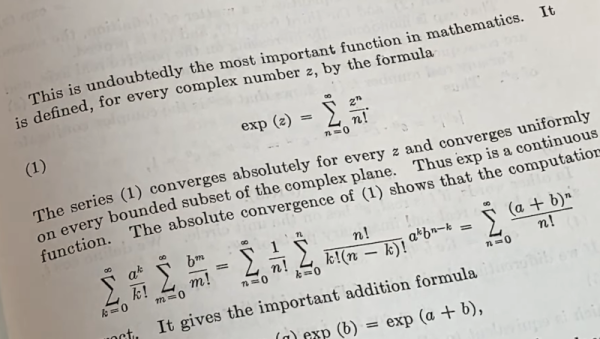

For those unfamiliar with it, AoE, first published in 1980, is an unusually useful hybrid of textbook and engineer’s reference, blending just enough theory with liberal doses of practical experience. With its lively tone and informal style, the book has enabled people from many backgrounds to design and implement electronic circuits.

After the initial book, the second edition (AoE2) was published in 1989, and the third (AoE3) in 2015, each one renewing and expanding coverage to keep up with the rapid pace of the field. I started with the second edition and it was very well worn when I purchased a copy of the third, an upgrade I would recommend to anyone still on the fence. While the second and third books looked a lot like the first, this new one is a bit different. It’s at the same time an expanded discussion of many of the topics covered in AoE3 and a self-contained reference manual on a variety of topics in electrical engineering.

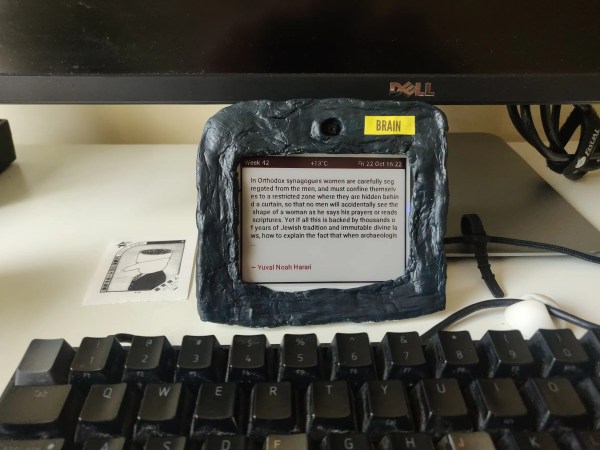

I pre-ordered this book the same day I learned it was to be published, and it finally arrived this week. So, having had the book in hand — almost continuously — for a few days, I think I’ve got a decent idea of what it’s all about. Stick around for my take on the latest in this very interesting series of books.

Continue reading “The Truth Is In There: The Art Of Electronics, The X-Chapters” →