For decades there has been this tantalizing idea being pitched of pulling CO2 out of the air and using the carbon molecules for something more useful, like making plastics. Although this is a fairly simple process, it is also remarkably inefficient. Recently Caltech researchers have managed to boost the efficiency somewhat with a new two-stage process involving electrocatalysis and thermocatalysis that gets a CO2 utilization of 14%, albeit with pure CO2 as input.

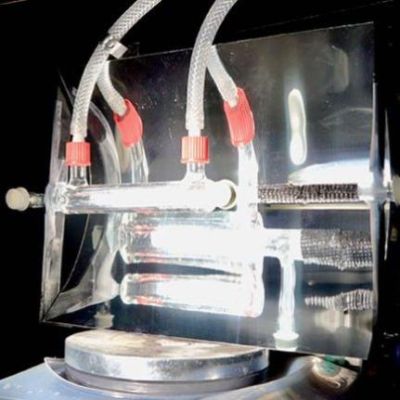

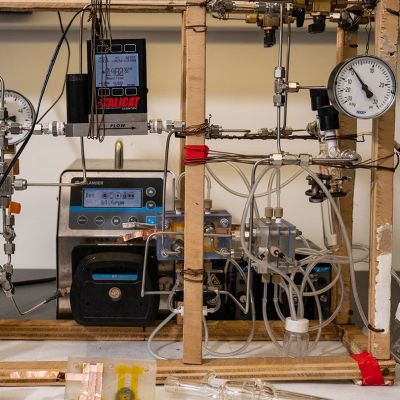

The full paper as published in Angewandte Chemie International is sadly paywalled with no preprint available, but we can look at the Supplemental Information for some details. We can see for example the actual gas diffusion cell (GDE) starting on page 107 in which the copper and silver electrodes react with CO2 in a potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3) aqueous electrolyte, which produces carbon monoxide (CO) and ethylene (C2H4). These then react under influence of a palladium catalyst in the second step to form polyketones, which is already the typical way that these thermoplastics are created on an industrial scale.

The novelty here appears to be that the ethylene and CO are generated in the GDEs, which require only the input of CO2 and the potassium bicarbonate, with the CO2 recirculated for about an hour to build up high enough concentrations of CO and C2H4. Even so, the researchers note a disappointing final quality of the produced polyketones.

Considering that a big commercial outfit like Novomer that attempted something similar just filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, it seems right to be skeptical about producing plastics on an industrial scale, before even considering using atmospheric CO2 for this at less than 450 ppm.