Continuous glucose meters (CGMs) aren’t just widgets for the wellness crowd. For many, CGMs are real-time feedback machines for the body, offering glucose trendlines that help people rethink how they eat. They allow diabetics to continue their daily life without stabbing their fingertips several times a day, in the most inconvenient places. This video by [Becky Stern] is all about comparing two of the most popular continuous glucose monitors (CGMs): the Abbott Libre 3 and the Dexcom G7.

Both the Libre 3 and the G7 come with spring-loaded applicators and stick to the upper arm. At first glance they seem similar, but the differences run deep. The Libre 3 is the minimalist of both: two plastic discs sandwiching the electronics. The G7, in contrast, features an over-molded shell that suggests a higher production cost, and perhaps, greater robustness. The G7 needs a button push to engage, which users describe as slightly clumsy compared to the Libre’s simpler poke-and-go design. The nuance: G7’s ten-day lifespan means more waste than the fourteen-day Libre, yet the former allows for longer submersion in water, if that’s your passion.

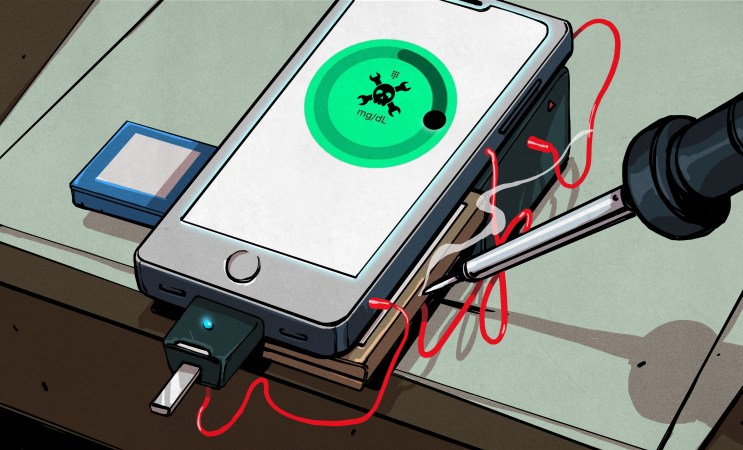

While these devices are primarily intended for people with diabetes, they’ve quietly been adopted by a growing tribe of biohackers and curious minds who are eager to explore their own metabolic quirks. In February, we featured a dissection of the Stelo CGM, cracking open its secrets layer by layer.

Continue reading “Peeking At Poking Health Tech: The G7 And The Libre 3”