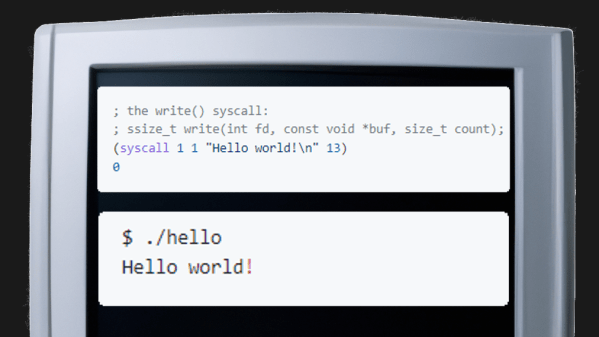

Ah, Lisp, the archaic language that just keeps on giving. You either love or hate it, but you’ll never stop it. [David Johnson-Davies] is clearly in the love it camp and, to that end, has produced a fair number of tools wedging this language into all kinds of nooks and crannies. The particular nook in question is the RISC-V ISA, with their Lisp-to-RISC-V compiler. This project leads on from their RISC-V assembler by allowing a Lisp function to be compiled directly to assembly and then deployed as callable, provided you stick to the supported language subset, that is!

The fun thing is—you guessed it—it’s written in Lisp. In fact, both projects are pure Lisp and can be run on the uLisp core and deployed onto your microcontroller of choice. Because who wouldn’t want to compile Lisp on a Lisp machine? To add to the fun, [David] created a previous project targeting ARM, so you’ve got even fewer excuses for not being able to access this. If you’ve managed to get your paws on the new Raspberry Pi Pico-2, then you can take your pick and run Lisp on either core type and still compile to native.

The Lisp-Risc-V project can be found in this GitHub repo, with the other tools easy enough to locate.

We see a fair few Lisp projects on these pages. Here’s another bare metal Lisp implementation using AVR. And how many lines of code does it take to implement Lisp anyway? The answer is 42 200 lines of C, to be exact.