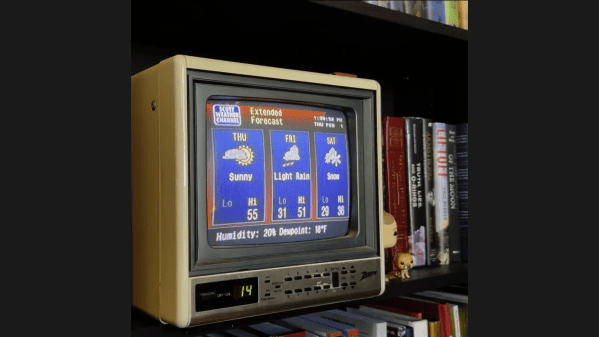

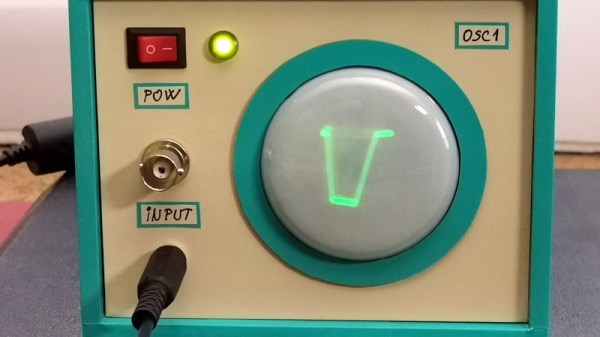

Here at Hackaday we’re a varied bunch of writers, some of whom have careers away from this organ, and others whose work also appears on the pages of other publications in different fields. One such is our colleague [Lewin Day], and he’s written a cracking piece for The Autopian about the effort to keep an obscure piece of American automotive electronic history alive. We think of big-screen control panels in cars as a new phenomenon, but General Motors was fitting tiny Sony Trinitron CRTs to some models back in the late 1980s. If you own one of these cars the chances are the CRT is inoperable if you’ve not encountered [Jon Morlan] and his work repairing and restoring them.

Lewin’s piece goes into enough technical detail that we won’t simply rehash it here, but it’s interesting to contrast the approach of painstaking repair with that of replacement or emulation. It would be a relatively straightforward project to replace the CRT with a modern LCD displaying the same video, and even to use a modern single board computer to emulate much of a dead system. But we understand completely that to many motor enthusiasts that’s not the point, indeed it’s the very fact it has a frickin’ CRT in the dash that makes the car.We’ll probably never drive a 1989 Oldsmobile Toronado. But we sure want to if it’s got that particular version of the future fitted.

Lewin’s automotive writing is worth watching out for. He once brought us to a motorcycle chariot.