Something odd is afoot in the mountains around Salt Lake City, Utah, at least according to local media reports of remote radio installations that have been popping up for at least the past year. The installations consist of a large-ish solar panel, a weatherproof box full of batteries — and presumably other electronics, including radios — and a mast bearing at least one antenna. Local officials aren’t quite sure who these remote setups belong to or what they’re intended to do, but the installations obviously represent a huge investment in resources.

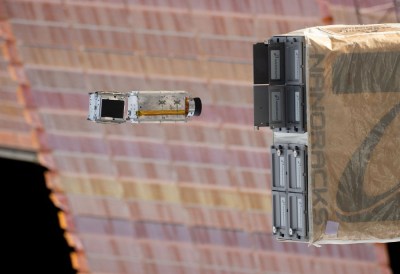

The one featured in the story was located near the summit of Twin Peaks, which is about 11,000 feet (3,300 meters) in elevation, which with that much gear was probably a hell of a hike. Plus, the owner took great pains to make sure the site would withstand the weather, with antenna mast guy wires that must have required lugging a pretty big drill up with them. There aren’t any photos of the radios in the enclosure, but one photo shows a 900-MHz LORA antenna, while another shows what appears to be a panel antenna, perhaps pointing toward another site. So maybe a LORA mesh network? Some comments in the Twitter thread show most people are convinced this is a Helium crypto mining rig, but the Helium Explorer doesn’t show any hotspots listed in that area. Either way, the owners are out of luck, since their gear is being removed if it’s on public land.