We’ll admit it. We have access to great debugging tools and, yes, sometimes they are invaluable. But most of the time, we’ll just throw a few print statements in whatever program we’re running to better understand what’s going on inside of it. [Loop Invariant] wants to point out to us that there are things a proper debugger can do that you can’t do with print statements.

So what are these magical things? Well, some of them depend on the debugger, of course. But, in general, debuggers will catch exceptions when they occur. That can be a big help, especially if you have a lot of them and don’t want to write print statements on every one. Semi-related is the fact that when a debugger stops for an exception or even a breakpoint, you can walk the call stack to see the flow of code before you got there.

In fact, some debuggers can back step, although not all of them do that. Another advantage is that you can evaluate expressions on the fly. Even better, you should be able to alter program flow, jumping over some code, for example.

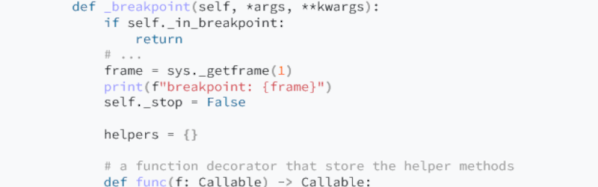

So we get it. There is more to debugging than just crude print statements. Then again, there are plenty of Python libraries to make debug printing nicer (including IceCream). Or write your own debugger. If gdb’s user interface puts you off, there are alternatives.