Al and I were talking on the podcast about Dan Maloney’s recent piece on how lead and silver are refined and about the possibility of anyone fully understanding a modern cellphone. This lead to Al wondering at the complexity of the constructed world in which we live: If you think hard enough about anything around you right now, you’d probably be able to recreate about 0% of it again from first principles.

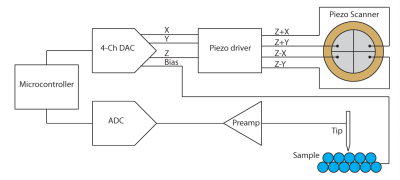

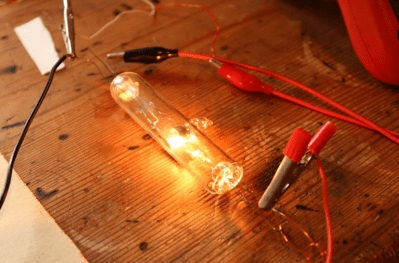

Smelting lead and building a cellphone are two sides of coin, in my mind. The process of getting lead out of galena is simple enough to comprehend, but it’s messy and dangerous in practice. Cellphones, on the other hand, are so monumentally complex that I’d wager that no single person could even describe all of the parts in sufficient detail to reproduce them. That’s why they’re made by companies with hundreds of engineers and decades of experience with the tech – the only way to build a cellphone is to split the complicated task into many subsystems.

Smelting lead and building a cellphone are two sides of coin, in my mind. The process of getting lead out of galena is simple enough to comprehend, but it’s messy and dangerous in practice. Cellphones, on the other hand, are so monumentally complex that I’d wager that no single person could even describe all of the parts in sufficient detail to reproduce them. That’s why they’re made by companies with hundreds of engineers and decades of experience with the tech – the only way to build a cellphone is to split the complicated task into many subsystems.

Smelting lead is a bad DIY project because it’s simple in principle, but prohibitive in practice. Building a cellphone from the ground up is incomprehensible in principle, but ironically entirely doable in practice if you’re willing to buy into some abstractions.

Indeed, last week we saw a nearly completely open-source build of a simple smartphone, and the secret to making it work is knowing the limits of DIY. The cell modem, for instance, is a black box. It’s an abstract device that you can feed data to and read data from, and it handles the radio parts of the phone that would take forever to design from scratch. But you don’t need to understand its inner workings to use it. Knowing where the limits of DIY are in your project, where you’re willing to accept the abstraction and move on, can be critical to getting it done.

Of course, in an ideal world, you’d want the cell modem to be like smelting lead – something that’s possible to understand in principle but just not worth DIYing in practice. And of course, there are some folks out there who hack on cell modem firmware and others who could do the radio engineering. But despite my strong DIY urges, I’d have to admit that the essential complexity of the module simply makes it worth treating as a black box. It’s very probably the practical limit of DIY.