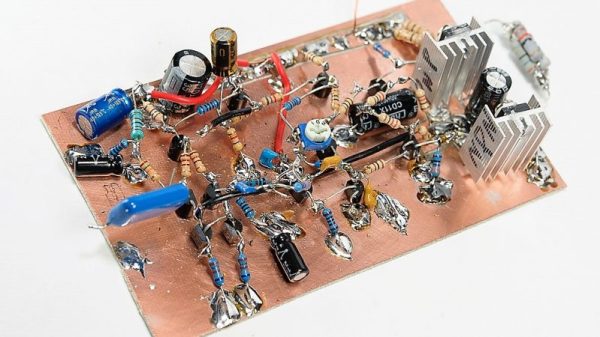

Ever since a Dutch businessman peered into the microscopic world through his brass and glass contraption in the 1600s, microscopy has had a long, rich history of DIY innovation. This DIY fluorescence microscope is another step along that DIY path that might just open up a powerful imaging technique to amateur scientists and biohackers.

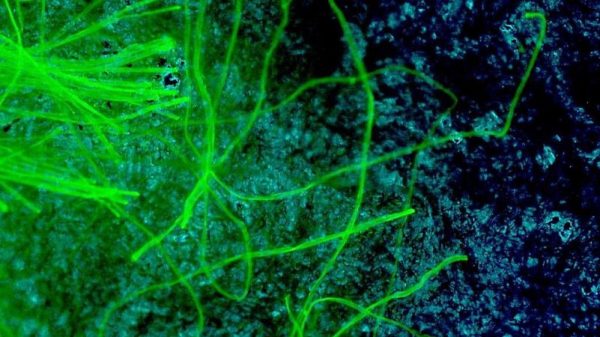

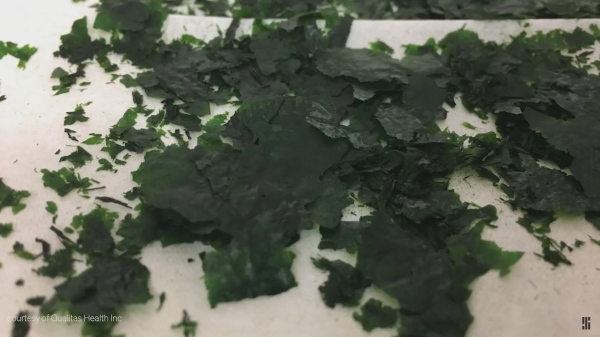

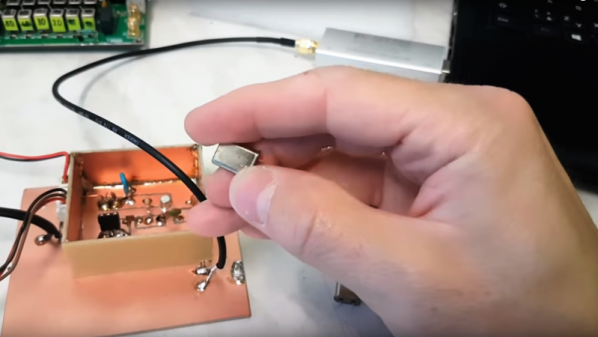

In fluorescence microscopy, cells are treated with various fluorescent dyes that can be excited with light at one wavelength and emit light at another. But as [Jonathan Bumstead] points out, fluorescence microscopes are generally priced out of the range of biohackers. His homebrew scope levels the playing field a bit. The trick is to use 3D-printed parts to kit out commonly available digital cameras – a USB microscope, a DSLR, or even a smartphone camera. Excitation is provided by a ring of Nexopixel LEDs, while a movable rack holds a filter that blocks the excitation wavelength but allows the emission wavelength to pass through to the camera. He demonstrates the technique by staining some threads with fluorescent ink from a highlighter marker and placing them on a sheet of tissue paper; in conventional bright-field mode, the threads all but disappear into the background, but jump right out under fluorescence.

Ith’s true that the optics are not exactly lab quality, and the microscope is currently only set up to do reflectance imaging as opposed to the more typical transmissive mode where the light passes through the sample. That’s an easy fix, though, and reflectance mode is still useful. We’ve seen fluorescence microscopy get quite complex before, but this simple scope might be enough to get a biohacker started.

Continue reading “See Cells In A New Light With A DIY Fluorescence Microscope”