As of about a day ago, Google’s reasonably new Find My network just got more useful. [Leon Böttger] released his re-implementation of the Android tracker network: GoogleFindMyTools. Most interestingly for us, there is example code to turn an ESP32 into a trackable object. Let the games begin!

Everything is in its first stages here, and not everything has been implemented yet, but you are able to query devices for their keys, and use this to decrypt their latest location beacons, which is the main use case.

The ESP32 code appears not to support MAC address randomization just yet, so it’s possibly more trackable than it should be, but if you’re just experimenting with the system, this shouldn’t be too much of a problem. The README also notes that you might need to re-register after three days of use. We haven’t gotten to play with it just yet. Have you?

If you’re worried about the privacy implications of yet another ubiquitous tracking system out there, you’re not alone. Indeed, [Leon] was one of the people working on the Air Guard project, which let iPhone users detect trackers of all sorts around them. Anyone know if there’s something like that for Android?

Thanks [Lars] for the hot tip!

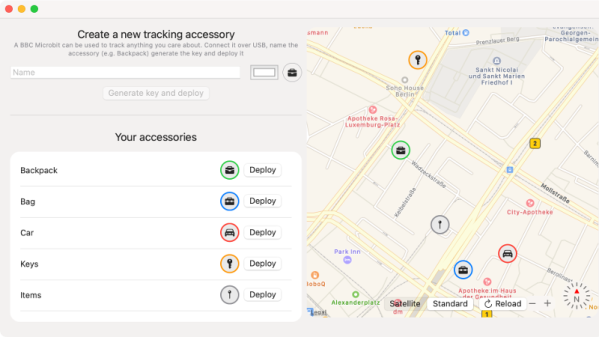

Somewhat ironically, while OpenHaystack allows you to track non-Apple devices on the Find Me tracking network, you will need a Mac computer to actually see where your device is. The team’s software requires a computer running macOS 11 (Big Sur) to run, and judging by the fact it integrates with Apple Mail to pull the tracking data through a private API, we’re going to assume this isn’t something that can easily be recreated in a platform-agnostic way.

Somewhat ironically, while OpenHaystack allows you to track non-Apple devices on the Find Me tracking network, you will need a Mac computer to actually see where your device is. The team’s software requires a computer running macOS 11 (Big Sur) to run, and judging by the fact it integrates with Apple Mail to pull the tracking data through a private API, we’re going to assume this isn’t something that can easily be recreated in a platform-agnostic way.