[CuriousMarc] is back with more vintage HP hardware repair. This time it’s the HP 5245L, a digital nixie-display frequency counter from 1963. This unit is old enough to be entirely made of discrete components, but has a real trick up its sleeve, with add-on components pushing the frequency range all the way up to 18 GHz. But this poor machine was in rough shape. There were previous repair attempts, some of which had to be re-fixed with proper components. When it hit [Marc]’s shop, the oscillator was working, as well as the frequency divider, but the device wasn’t counting, and the reference frequencies weren’t testing good at the front of the machine. There were some of the usual suspects, like blown transistors. But things got really interesting when one of the boards had a couple of tarnished transistors, and a handful of nice shiny new ones — but maybe not all the right transistors. Continue reading “Do Not Attempt Disassembly: Analog Wizardry In A 1960s Counter”

frequency counter34 Articles

To Turn An ATtiny817 Into A 150MHz Counter, First Throw Out The Spec Sheet

One generally reads a data sheet in one of two ways. The first is to take every spec at face value, figuring that the engineers have taken everything into account and presented each number as the absolute limit that will prevent the Magic Smoke from escaping. The other way is to throw out the data sheet and just try whatever you want, figuring that the engineers played it as safely as possible.

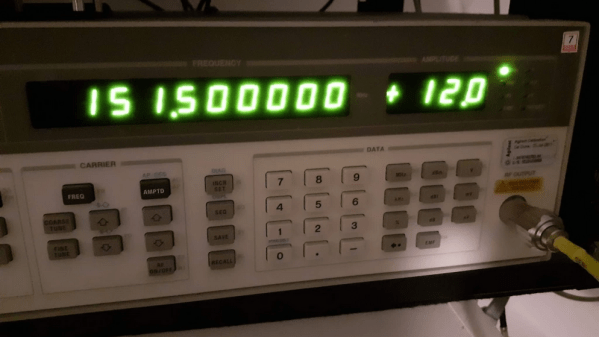

The latter case seems to have been the motivation behind pushing an ATtiny way, WAY beyond what the spec sheet says is possible. According to [SM6VFZ], the specs on the ATtiny817 show that the 12-bit timer/counter D (TCD) should be limited to a measly 32 MHz maximum frequency, above which one is supposed to employ the counter’s internal prescaler. But by using a 10-MHz precision frequency generator as an external clock, [SM6VFZ] found that inputs up to slightly above 151 MHz were countable with 1-Hz precision. Above that point, things started to drift, but that’s still pretty great performance from something cobbled together on an eval board in a decidedly suboptimal way.

We’d imagine this result could lead to some interesting projects, since the undocumented limit for this timer puts it well within range of multiple amateur radio allocations. Even if it doesn’t prove useful, that’s OK — just seeing how far things can be pushed is cool too. And it’s not like this is the first time we’ve caught [SM6VFZ] persuading an ATtiny to do unusual things, either.

Clock Testing Sans Oscilloscope?

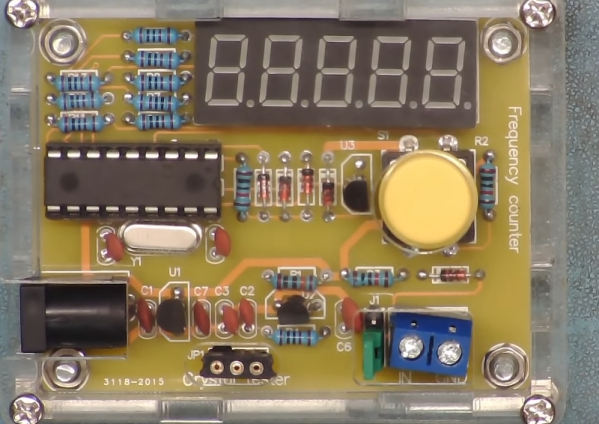

Like many people who repair stuff, [Learn Electronics Repair] has an oscilloscope. But after using it to test a motherboard crystal oscillator, he started thinking about how people who don’t own a scope might do the same kind of test. He picked up a frequency counter/crystal tester kit that was quite inexpensive — under $10. He built it, and then tried it to see how well it would work in-circuit.

The kit has an unusual use of 7-segment displays to sort-of display words for menus. There is a socket to plug in a crystal for testing, but that won’t work for the intended application. He made a small extender to simplify connecting crystals even if they are surface mount. He eventually added a BNC socket to the counter input, but at first just wired some test leads directly in.

Edge-Mounted Meters Give This Retro Frequency Counter Six Decades Of Display

With regard to retro test gear, one’s thoughts tend to those Nixie-adorned instruments of yore, or the boat-anchor oscilloscopes that came with their own carts simply because there was no other way to move the things. But there were other looks for test gear back in the day, as this frequency counter with a readout using moving-coil meters shows.

We have to admit to never seeing anything like [Charles Ouweland]’s Van Der Heem 9908 electronic counter before. The Netherlands-based company, which was later acquired by Philips, built this six-digit, 1-MHz counter sometime in the 1950s. The display uses six separate edge-mounted panel meters numbered 0 through 9 to show the frequency of the incoming signal. The video below has a demo of what the instrument can do; we don’t know if it was restored at some point, but it still works and it’s actually pretty accurate. Later in the video, he gives a tour of the insides, which is the real treat — the case opens like a briefcase and contains over 20 separate PCBs with a bunch of germanium transistors, all stitched together with point-to-point wiring.

We appreciate the look inside this unique piece of test equipment history. It almost seems like something that would have been on the bench while this Apollo-era IO tester was being prototyped.

Continue reading “Edge-Mounted Meters Give This Retro Frequency Counter Six Decades Of Display”

NTP, Rust, And Arduino Make A Phenomenal Frequency Counter

Making a microcontroller perform as a frequency counter is a relatively straightforward task involving the measurement of the time period during which a number of pulses are counted. The maximum frequency is however limited to a fraction of the microcontroller’s clock speed and the accuracy of the resulting instrument depends on that of the clock crystal so it will hardly result in the best of frequency counters. It’s something [FrankBuss] has approached with an Arduino-based counter that offloads the timing question to a host PC, and thus claims atomic accuracy due to its clock being tied to a master source via NTP. The Rust code PC-side provides continuous readings whose accuracy increases the longer it is left counting the source. The example shown reaches 20 parts per billion after several hours reading a 1 MHz source.

It’s clear that this is hardly the most convenient of frequency counters, however we can see that it could find a use for anyone intent on monitoring the long-term stability of a source, and could even be used with some kind of feedback to discipline an RF source against the NTP clock with the use of an appropriate prescaler. Its true calling might come though not in measurement but in calibration of another instrument which can be adjusted to match its reading once it has settled down. There’s surely no cheaper way to satisfy your inner frequency standard nut.

Easy Frequency Counter Looks Good, Reads To 6.5 MHz

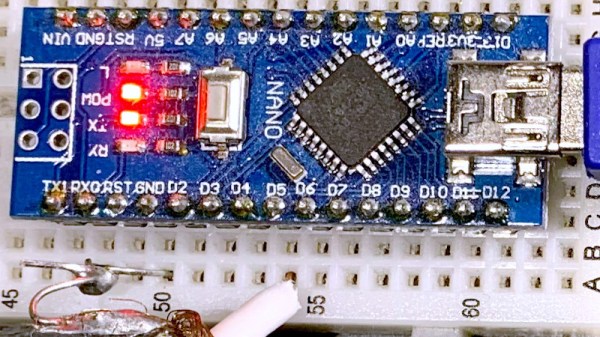

We were struck by how attractive [mircemk’s] Arduino-based frequency counter looks. It also is a reasonably simple build. It can count up to 6.5 MHz which isn’t that much, but there’s a lot you can do even with that limitation.

The LED display is decidedly retro. Inside a very modern Arduino Nano does most of the work. There is a simple shaping circuit to improve the response to irregular-shaped input waveforms. We’d have probably used a single op-amp as a zero-crossing detector. Admittedly, that’s a bit more complex, but not much more and it should give better results.

Continue reading “Easy Frequency Counter Looks Good, Reads To 6.5 MHz”

Radio Shack Shortwave Goes Digital

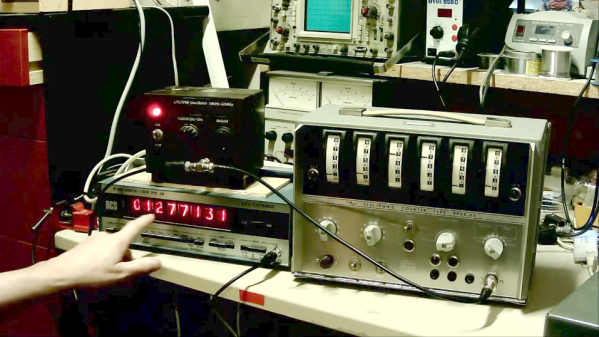

If you spent the 1970s obsessively browsing through the Radio Shack catalog, you probably remember the DX-160 shortwave receiver. You might have even had one. The radio looked suspiciously like the less expensive Eico of the same era, but it had that amazing-looking bandspread dial, instead of the Eico’s uncalibrated single turn knob number 1 to 10. Finding an exact frequency was an artful process of using both knobs, but [Frank] decided to refit his with a digital frequency display.

Even if you don’t have a DX-160, the techniques [Frank] uses are pretty applicable to old receivers like this. In this case, the radio is a single conversion superhet with a variable frequency oscillator (VFO), so you need only read that frequency and then add or subtract the IF before display. If you can find a place to tap the VFO without perturbing it too much, you should be able to pull the same stunt.