To our younger readers, a car without an all-touchscreen “infotainment” system may look clunky and dated, but really, you kids don’t know what they’re missing. Buttons, knobs, and switches all offer a level of satisfying tactility and feedback that touchscreens totally lack. [Garage Tinkering] on YouTube agrees; he also doesn’t like the way his aftermarket Kenwood head unit looks in his 2004-vintage Nissan. That’s why he decided to take matters into his own hands, and hack the buttons back on.

Rather than source a vintage stereo head unit, or try and DIY one from scratch, [Garage Tinkering] has actually hidden the modern touchscreen unit behind a button panel. That button panel is actually salvaged from the stock stereo, so the looks fit the car. The stereo’s LCD gets replaced with a modern color unit, but otherwise it looks pretty stock at the end.

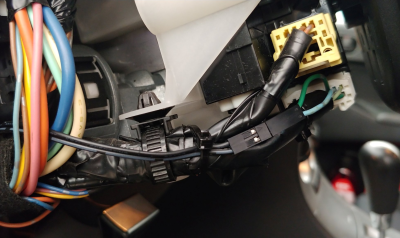

Adding buttons to the Kenwood is all possible thanks to steering-wheel controls. In order to make use of those, the touchscreen head unit came with a little black box that translated the button press into some kind of one-wire protocol that turned out to be an inverted and carrier-less version of the NEC protocol used in IR TV remotes. (That bit of detective work comes from [michaelb], who figured all this out for his Ford years ago, but [Garage Tinkering] is also sharing his code on GitHub.) Continue reading “Hacking Buttons Back Into The Car Stereo”