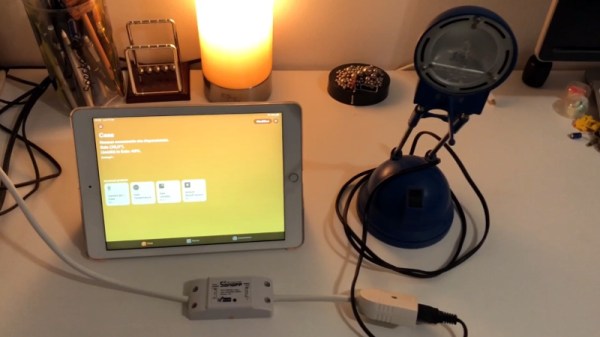

There’s certainly no shortage of “smart” gadgets out there that will provide you with a notification, or even a live audiovisual stream, whenever somebody is at your door. But as we’ve seen countless times before, not everyone is thrilled with the terms that most of these products operate under. Getting a notification on your phone when the pizza guy shows up shouldn’t require an email address, credit card number, or DNA sample.

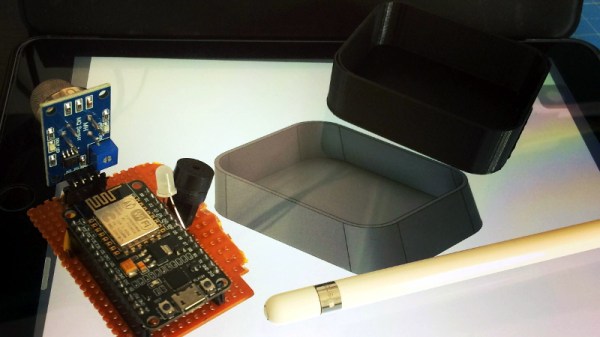

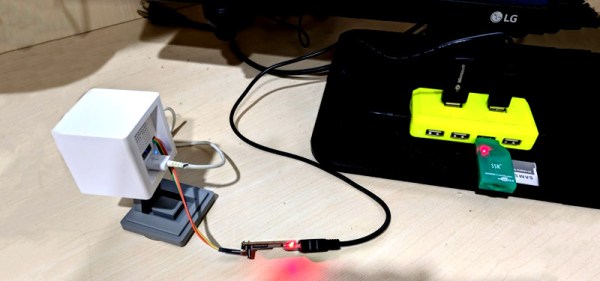

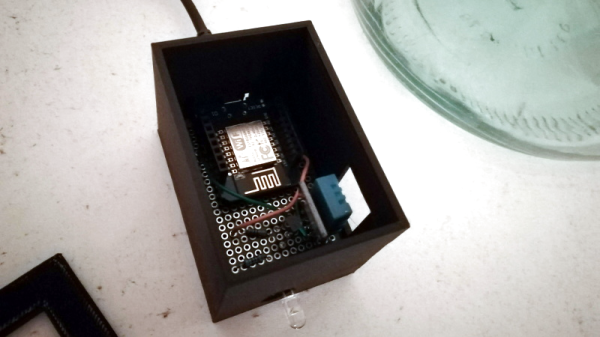

For [Nick Touran], half the work was already done. There was already a traditional wired doorbell in his home, he just had to come up with a minimally invasive way to link it with Home Assistant. He reasoned that he could tap into the low-voltage side of the doorbell transformer and watch for the telltale fluctuations that would indicate the bell was doing its thing. The ESP8266 has an ADC to measure voltage and WiFi to connect to Home Assistant, so it seemed like the perfect bridge between old and new.

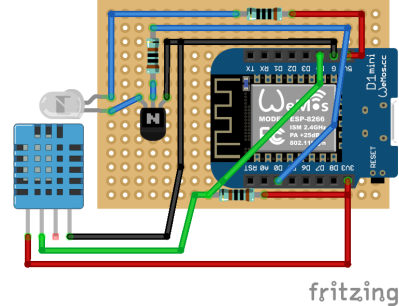

Of course, as with any worthwhile project, it ended up being a bit more complicated. Wired doorbells generally operate on 16-24 VAC, and [Nick] knew if he tried to put his Wemos D1 across the line he’d release the critical Magic Smoke. What he needed was a voltage divider circuit that would take low-voltage AC and drop it to an even lower DC voltage that the microcontroller could cope with.

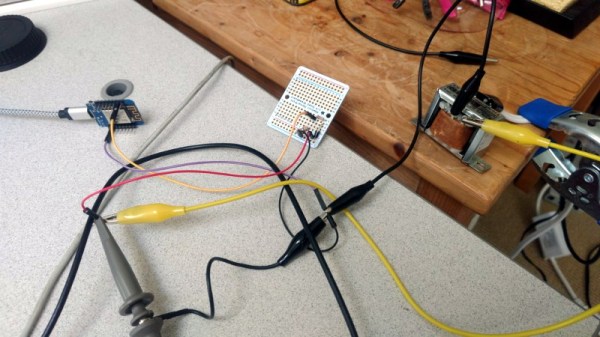

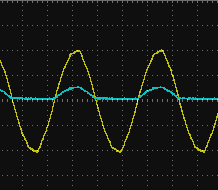

The simple circuit [Nick] comes up with cuts the voltage way down and removes the negative component completely. So what was originally 18.75 VAC turned into a series of 60 Hz blips at 2.4 VDC; perfect for feeding into a microcontroller ADC. With a baseline to work from, he could then write some code that would watch for variations in this signal to determine when the bell was ringing.

Or at least, that was the idea. While the setup worked well enough on the bench, its performance in the real-world left something to be desired. If his house guest had a heavy hand, it worked great. But a quick tap of the doorbell button would tend to go undetected. After investigating the issue, [Nick] found that he needed to use some software trickery to ensure the ESP8266 was able to keep up with the speedy signal. Once he was able to reliably detect short and long button presses, the rest was just a simple matter of sending an MQTT message to his automation system.

Compared to the hoops we’ve seen other hackers have to jump through to smarten up their doorbells, we think [Nick] got off fairly easy. This project is also an excellent example of how learning about circuit design and passive components can still come in handy in the Arduino Era.

Continue reading “Sniffed Transformer Puts Wired Doorbell Online”