When it comes to the “build versus buy” question, “buy” almost always wins. The amount of time you have to put into building something is rarely justified, especially with a world of options available at the click of a mouse.

That’s not always the case, of course. These custom-made linear actuators are a perfect example of when building your own wins. For a planned ball-juggling robot, [Harrison Low] found himself in need of linear actuators with long throw distance, high speed, and stiff construction. Nothing commercially available checked all the boxes, so he set out to design his own.

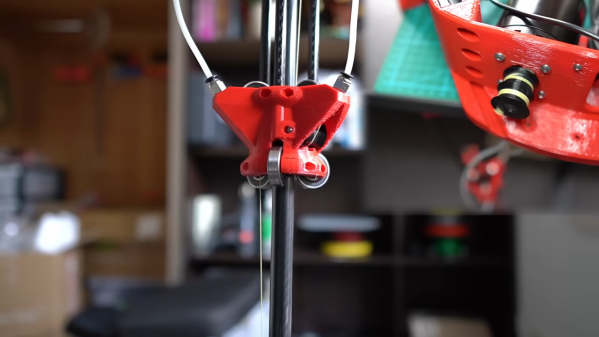

A few design iterations later, [Harrison] arrived at the actuators you see in the video below. Built mainly from carbon fiber tubing and 3D-printed parts, the actuators have about 30 centimeters of throw, and thanks to their cable-drive design, they’re pretty fast — much faster than his earlier lead screw designs. The stiffness of the actuator comes by way of six bearings to guide the arm, arranged in two tiers of three, each offset by 60 degrees. Along with some clever eccentric spacers to fine-tune positioning, this design provides six points of contact that really lock the tube into place.

The cable drive system [Harrison] used is pretty neat too. A Kevlar kite string is attached to each end of the central tube and then through PTFE tubes to a pulley on an ODrive BLDC, which extends and retracts the actuator. It’s a clever design in that it keeps the weight of the motor away from the actuator, but it does have its problems, as [Harrison] admits. Still, the actuator works great, and it looks pretty cool while doing it. CAD and code are available if you want to roll your own.

These actuators are cool enough, but the real treat here will be the ball juggler [Harrison] is building. We’ve seen a few of those before, but this one looks like it’s going to be mighty impressive.

Continue reading “Carbon Fiber And Kevlar Make This Linear Actuator Fast And Strong” →