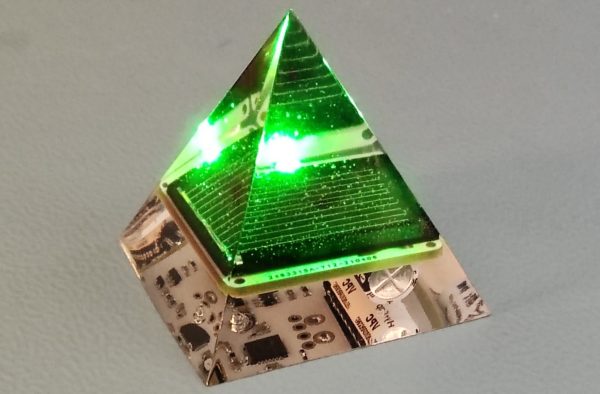

Without knowing it, we’ve spent years watching [Jasper Sikken] piece together an empire of energy harvesting equipment, and now he’s putting the pieces together into wonderful creations. His recently finished solar harvesting pyramids are mesmerizing objects of geometric perfection we’d love to see glinting in the sun.

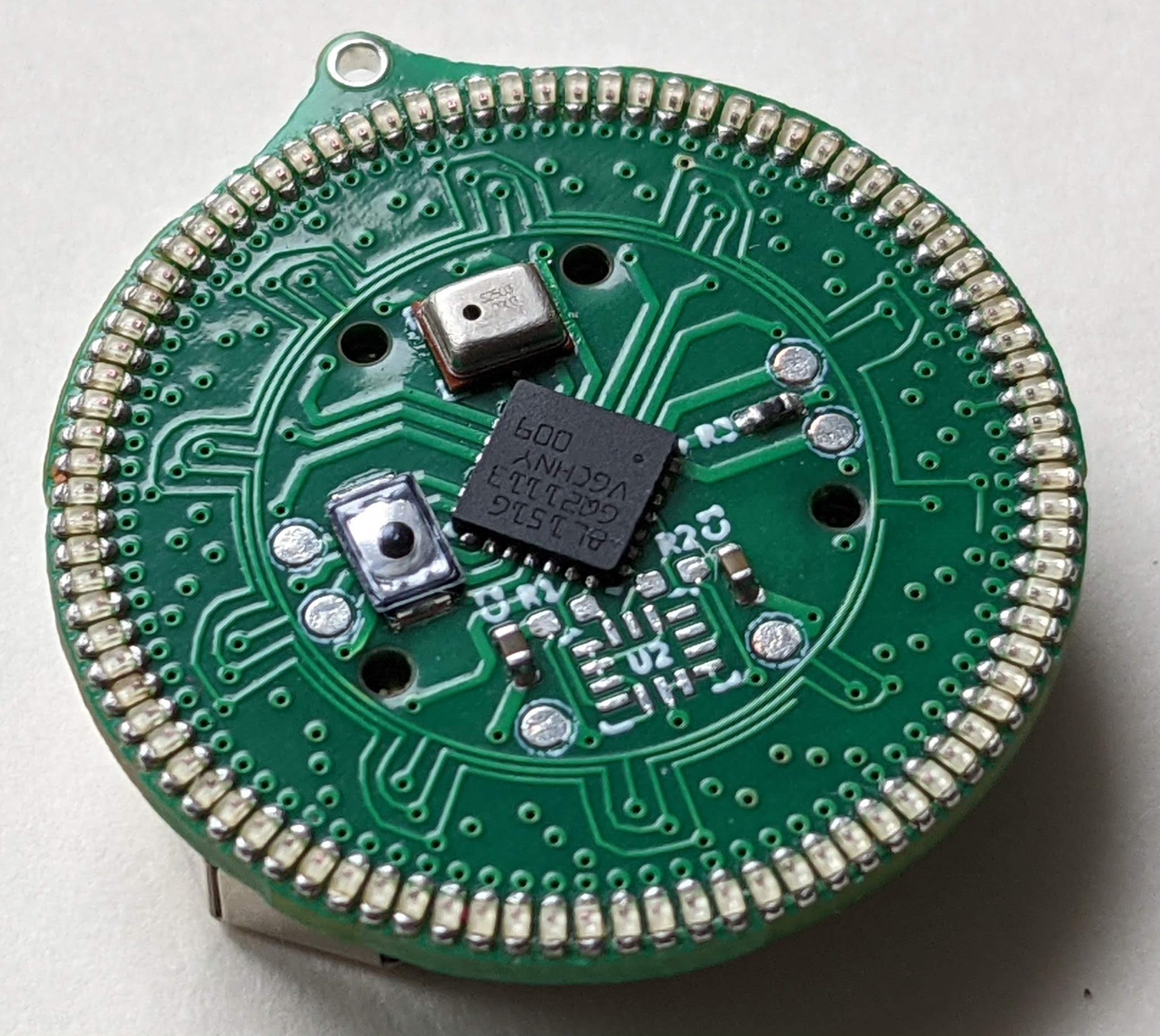

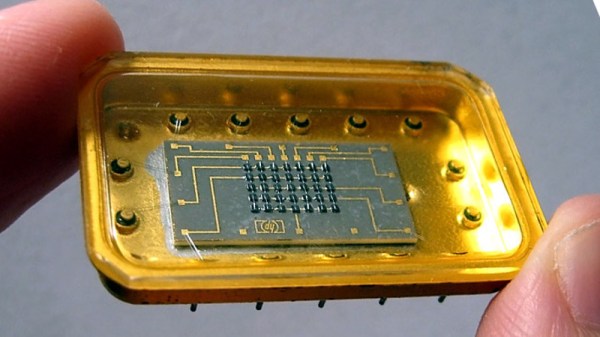

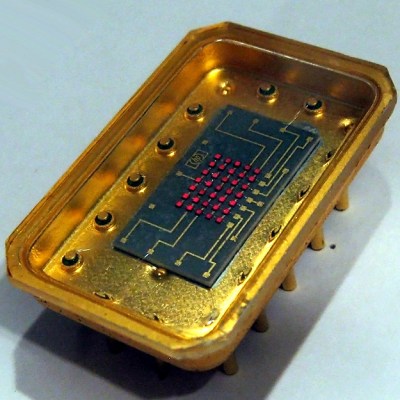

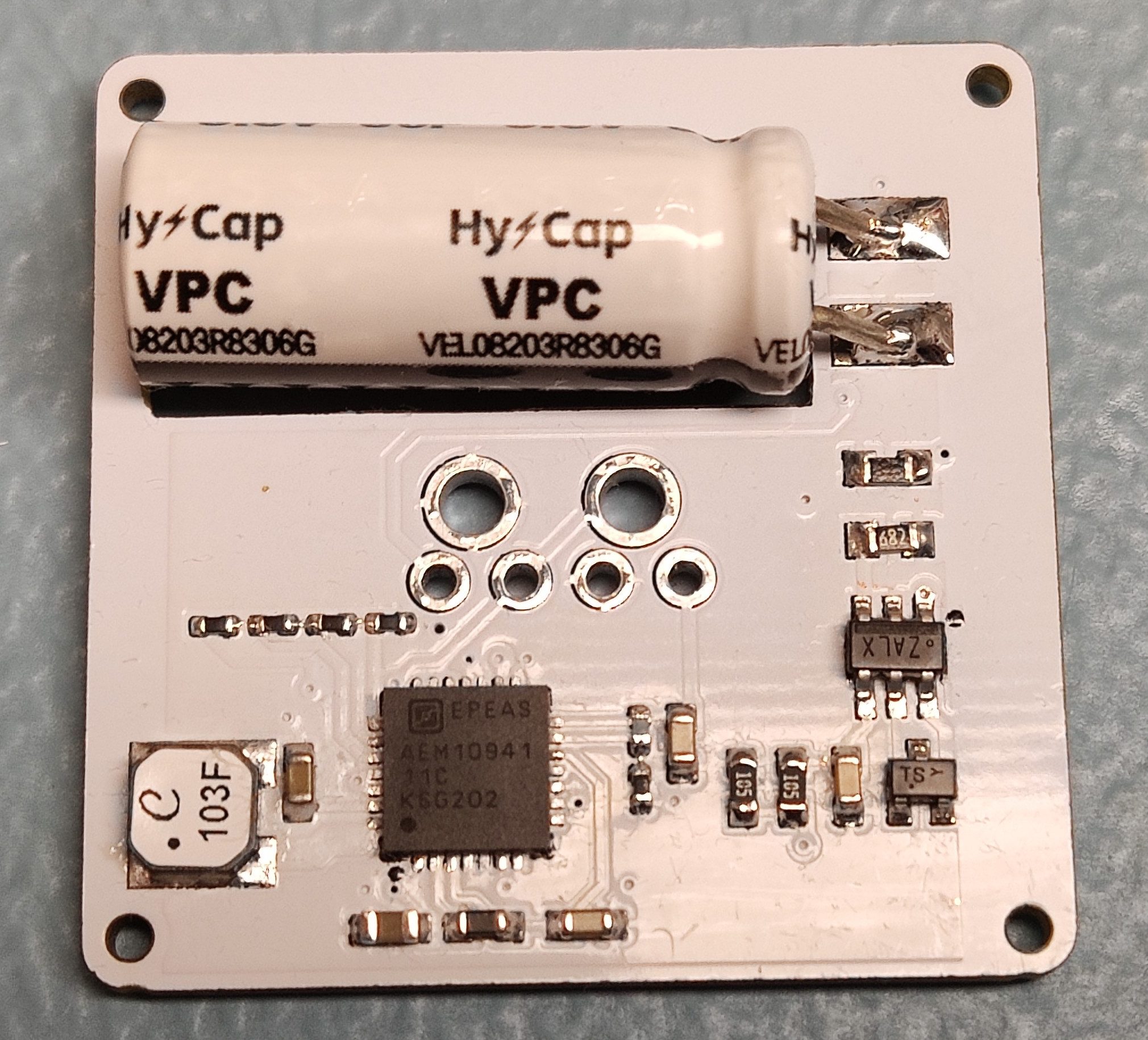

These solar harvesting pyramids are well described by their name. Each one contains a PCBA around 30mm on a side with a solar energy harvester built around the dedicated AEM10941 IC, a single solar cell, and a very bright green LED. [Jasper] calculates that the solar cell will charge the super capacitor at 20uA at with just 200 lux of light (a level typical for casual indoor spaces) letting it run indefinitely when placed indoors. Amazingly with the LED blinking for 15ms every 2 seconds it will run for 21 days in complete darkness. And that’s it! This is a software-free piece of hardware which requires no input besides dim light and blinks an LED indefinitely.

What about that super capacitor? It’s called a Lithium Ion Capacitor (LIC) and is a hybrid between a typical rechargeable lithium battery and an electrolytic capacitor, offering extremely high capacity in a convenient two leg through hole form factor. This one is a whopping 30 Farad at 3.8 V, and we first saw it when [Jasper] won the Hackaday Earth Day contest last month. Check out that link if you want to know more about their uses and how to integrate them.

For more detail about all of the components of the solar pyramid we need only turn to the Hackaday archives. In December 2019 [Tom Nardi] wrote about building a cheap degassing system for making some very familiar looking resin pyramids. And before that [Donald Papp] brought us another familiar piece of the pyramid when he wrote up a different 1″ x 1″ solar harvesting system that [Jasper] designed.

Check out the video after the break to see what one of these gems looks like from all sides. And for many more experiments leading up the final pyramid check out the logs on the Hackaday.io page.

Continue reading “Magic Pyramids Blink Eternal With The Power Of The Sun”