For companies that build equipment like CNC machines or lasercutters, it’s tempting to use open-source software in a lot of areas. After all, it’s stable, featureful, and has typically passed the test of time. But using open-source software is not always without attendant responsibilities. The GPL license requires that all third-party changes shipped to users are themselves open-sourced, with possibility for legal repercussions. But for that, someone has to step up and hold them accountable.

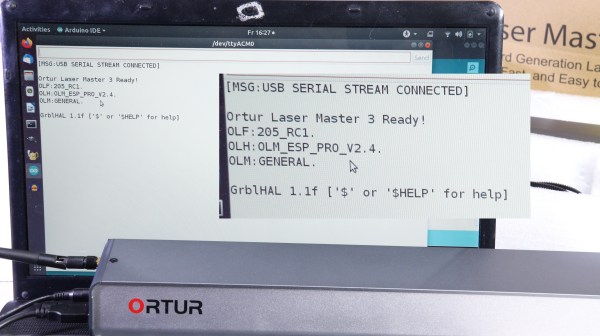

Here, the manufacturer under fire is Ortur. They ship laser engravers that quite obviously use the Grbl firmware, or a modified version thereof, so [Norbert] asked them for the source code. They replied that it was a “business secret”. He even wrote them a second time, and they refused. Step three, then, is making a video about it.

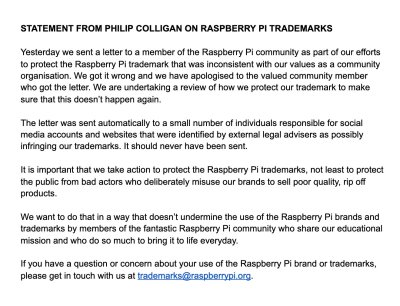

Unfortunately [Norbert] doesn’t have the resources to start international legal enforcement, so instead he suggests we should start talking openly about the manufacturers involved. This makes sense, since such publicity makes it way easier for a lawsuit eventually happen, and we’ve seen real consequences come to Samsung, Creality and Skype, among others.

Many of us have fought with laser cutters burdened by proprietary firmware, and while throwing the original board out is tempting, you do need to invest quite a bit more energy and money working around something that shouldn’t have been a problem. Instead, the manufacturers could do the right, and legal, thing in the first place. We should let them know that we require that of them.

Continue reading “Watch Out For Lasercutter Manufacturers Violating GPL”