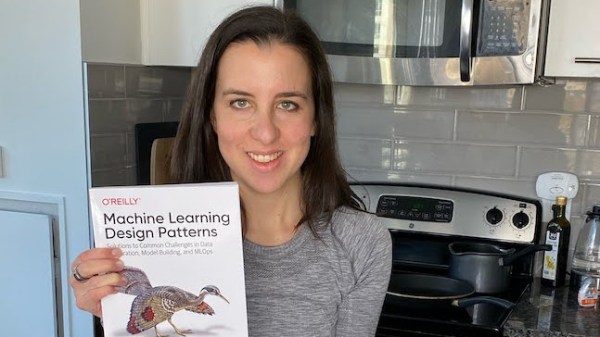

Ever wondered what, exactly, goes into creating a technical book? If you’d like to know the steps that bring a book from idea to publication, [Sara Robinson] tells all about it as she explains what went into co-authoring O’Reilly’s Machine Learning Design Patterns.

Her post was written in 2020, but don’t let that worry you, because her writeup isn’t about the book itself so much as it is about the whole book-writing process, and her experiences in going through it. (By the way, every O’Reilly book has a distinctive animal on the cover, and we learned from [Sara] that choosing the cover animal is a slightly mysterious process, and is not done by the authors.)

It turns out that there are quite a few steps that need to happen — like proposals and approvals — before the real writing even starts. The book writing itself is a process, and like most processes to which one is new, things start out slow and inefficient before they improve.

[Sara] also talks a bit about burnout, and her advice on dealing with it is as insightful as it is practical: begin by communicating honestly how you are feeling to the people involved.

Over the years I’ve learned that people will very rarely guess how you’re feeling and it’s almost always better to tell them […] I decided to tell my co-authors and my manager that I was burnt out. This went better than expected.

There is a lot of code in the book, and it has its own associated GitHub repository should you wish to check some of it out.

By the way, [Sara] celebrated publication by making a custom cake, which you can see near the bottom of her blog post. This comes as no surprise seeing as she has previously managed to combine machine learning with her love of making cakes!