Eggs are perhaps the most beloved staple of breakfast. However, they come with a flaw, they are incredibly messy to work with. Cracking in particular leaves egg on one’s hands and countertop, requiring frequent hand washing. This fundamental flaw of eggs inspired [Stuff Made Here] to fix it with an over-engineered egg cracking robot.

mechanical computer16 Articles

8 Bit Mechanical Computer Built From Knex

Long before electricity was a common household utility, humanity had been building machines to do many tasks that we’d now just strap a motor or set of batteries onto and think nothing of it. Transportation, manufacturing, agriculture, and essentially everything had non-electric analogs, and perhaps surprisingly, there were mechanical computers as well. Electronics-based computers are far superior in essentially every way, but the aesthetics of a mechanical computer are still unmatched, like this 8-bit machine built from K’nex.

Continue reading “8 Bit Mechanical Computer Built From Knex”

A 17th Century Music Computer

We don’t think of computers as something you’d find in the 17th century. But [Levi McClain] found plans for one in a book — books, actually — by [Athanasius Kirker] about music. The arca musarithmica, a machine to allow people with no experience to compose church music, might not fit our usual definition of a computer, but as [Levi] points out in the video below, there are a number of similarities to mechanical computers like slide rules.

Apparently, there are a few of these left in the world, but as you’d expect, they are quite rare. So [Levi] decided to take the plans from the book along with some information available publicly and build his own.

Clockwork Rover For Venus

Venus hasn’t received nearly the same attention from space programs as Mars, largely due to its exceedingly hostile environment. Most electronics wouldn’t survive the 462 °C heat, never mind the intense atmospheric pressure and sulfuric acid clouds. With this in mind, NASA has been experimenting with the concept of a completely mechanical rover. The [Beardy Penguin] and a team of fellow students from the University of Southampton decided to try their hand at the concept—video after the break.

The project was divided into four subsystems: obstacle detection, mechanical computer, locomotion (tracks), and the drivetrain. The obstacle detection system consists of three (left, center, right) triple-rollers in front of the rover, which trigger inputs on the mechanical computer when it encounters an obstacle over a certain size. The inputs indicate the position of each roller (up/down) and the combination of inputs determines the appropriate maneuver to clear the obstacle. [Beardy Penguin] used Simulink to design the logic circuit, consisting of AND, OR, and NOT gates. The resulting 5-layer mechanical computer quickly ran into the limits of tolerances and friction, and the team eventually had trouble getting their design to work with the available input forces.

Due to the high-pressure atmosphere, an on-board wind turbine has long been proposed as a viable power source for a Venus rover. It wasn’t part of this project, so it was replaced with a comparable 40 W electric motor. The output from a logic circuit goes through a timing mechanism and into a planetary gearbox system. It changes output rotation direction by driving the planet gear carrier with the sun gear or locking it in a stationary position.

As with many undergraduate engineering projects, the physical results were mixed, but the educational value was immense. They got individual subsystems working, but not the fully integrated prototype. Even so, they received several awards for their project and even came third in an international Simulink challenge. It also allowed another team to continue their work and refine the subsystems. Continue reading “Clockwork Rover For Venus”

Electronics Explained With Mechanical Devices

It can be surprisingly hard to find decent analogies when you’re teaching electronics basics. The water flow analogy, for instance, is decent for explaining Ohm’s law, but it breaks down pretty soon thereafter.

Hydraulics aren’t as easy to set up when you want an educational toykit for your child to play with, which leaves them firmly in the thought experiment area. [Steve Mould] shows us a different take – the experimentation kit called Spintronics, which goes the mechanical way, using chains, gears, springs and to simulate the flow of current and the effect of potential differences.

Through different mechanical linkages between gears and internal constructs, you can implement batteries, capacitors, diodes, inductors, resistors, switches, transistors, and the like. The mechanical analogy is surprisingly complete. [Steve] starts by going through the ways those building blocks are turned into mechanical-gear-based elements. He then builds one circuit after another in quick succession, demonstrating just how well it maps to the day-to-day electronic concepts. Some of the examples are oscillators, high-pass filters, and amplifiers. [Steve] even manages to build a full-bridge rectifier!

In the end, he also builds a flip-flop and an XOR gate – just in case you were wondering whether you could theoretically build a computer out of these. Such a mechanical approach makes for a surprisingly complete and endearing analogy when teaching electronics, and an open-source 3D printable take on the concept would be a joy to witness.

Looking for something you could gift to a young aspiring mind? You don’t have to go store-bought – there are some impressive hackers who build educational gadgets, for you to learn from.

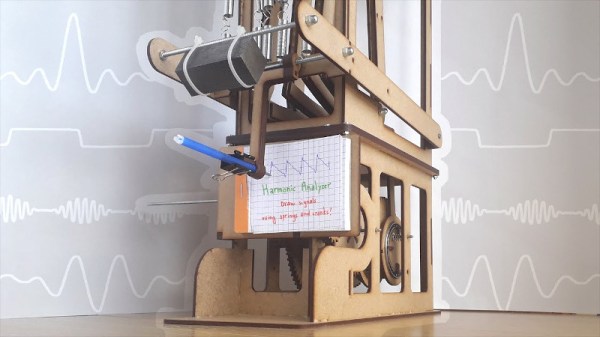

Harmonic Analyzer Does It With Cranks And Gears

Before graphic calculators and microcomputers, plotting functions were generally achieved by hand. However, there were mechanical graphing tools, too. With the help of a laser cutter, it’s even possible to make your own!

The build in question is nicknamed the Harmonic Analyzer. It can be used to draw functions created by adding sine waves, a la the Fourier series. While a true Fourier series is the sum of an infinite number of sine waves, this mechanical contraption settles on just 5.

This is achieved through the use of a crank driving a series of gears. The x-axis gearing pans the notepad from left to right. The function gearing has a series of gears for each of the 5 sinewaves, which work with levers to set the magnitude of the coefficients for each component of the function. These levers are then hooked up to a spring system, which adds the outputs of each sine wave together. This spring adder then controls the y-axis motion of the pen, which draws the function on paper.

It’s a great example of the capabilities of mechanical computing, even if it’s unlikely to ever run Quake. Other DIY mechanical computers we’ve seen include the Digi-Comp I and a wildly complex Differential Analyzer. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Harmonic Analyzer Does It With Cranks And Gears”

Teach Computing The Old-School Way With A Digi-Comp II

Ubiquitous computing has delivered a world in which there seem to be few devices left that no longer contain a microprocessor of some sort. Thus should a student wish to learn about the inner workings of a computer they can easily do so from a multitude of devices. For an earlier generation though this was not such a straightforward process, in the 1950s or 1960s you could not simply buy a microcomputer and set to work. Instead a range of ingenious teaching aids providing the essentials of computing without a computer were created, and those students saw their first computational logic through the medium of paper, ball bearings, or flashlight bulbs.

The DigiComp II was just such a device, performing logic tasks through ball bearings rolling down trackways. Genuine machines are now particularly rare, so [Mike Gardi] created a modern 3D printed replica that delivers all the fun without the cost. It’s a complicated build with a multitude of parts and wire linkages, and there is an element of fine tuning of its springs required to achieve reliable operation. You’ll neither run a Beowulf cluster of DigiComp IIs nor will you mine any Bitcoin with one, but it’s definitely one of the more unusual computing devices you could have in your collection.

Of course, should you need a truly authentic period computing device, there is always the slide rule.

Via Hacker News.