There’s more to making an oscillator than meets the eye, and [lcamtuf] is here with a good primer on the subject. It starts with the old joke that if you need an oscillator it’s best to try to make an amplifier instead, but of course the real point here is to learn how to make not just a mere oscillator, but a good oscillator.

He does this by taking the oscillator back to first principles and explaining positive feedback on an amplifier, before introducing the Schmitt trigger, an RC circuit to induce a delay, and then phase shift. These oscillators are not complex circuits by any means, so understanding their principles should allow you to unlock the secrets of oscillation in a less haphazard way than just plugging in values and hoping.

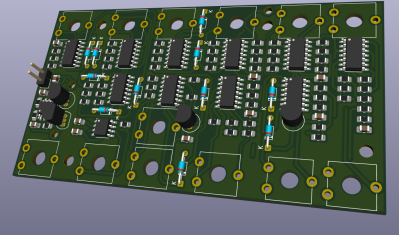

Oscillation is a subject we’ve taken a deep dive into ourselves here at Hackaday, should you wish to learn any more. Meanshile [lcamtuf] is someone we’ve heard from here before, with a comparative review of inexpensive printed circuit board manufacturers.