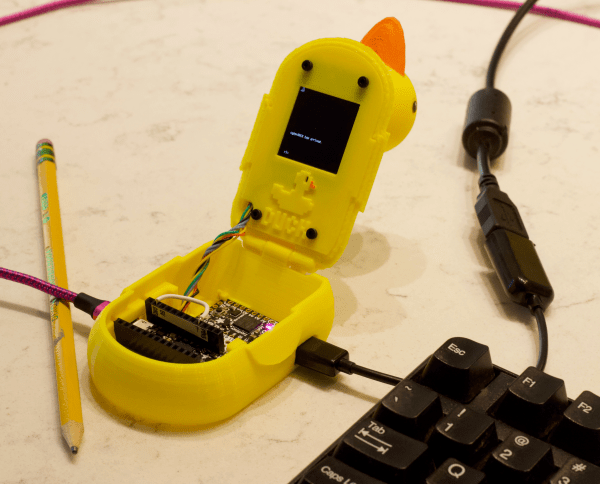

Choosing the perfect Linux distribution that satisfies your personal needs and likings can be an impossible task, and oftentimes requires a hint of Stockholm syndrome as compromise. In extreme cases, you might end up just rolling your own distro. But while frustration is always a great incentive for change, for [Josh Moore] it was rather curiosity and playful interest that led him to create snakeware, a Linux distribution where the entire user space not only runs on Python, but is Python.

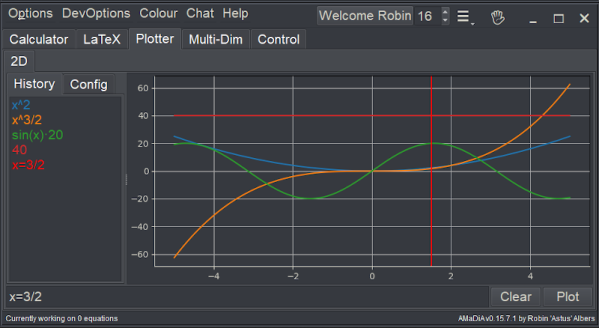

Imagine you would boot your Linux system, and instead of the shell of your choice, you would be greeted by an interactive Python interpreter, and everything you do on the system will be within the realms of that interpreter — that’s the gist of snakeware. Now, this might sound rather limiting at first, but keep in mind we’re talking about Python here, a language known for its versatility, with an abundance of packages that get things done quick and easy, which is exactly what [Josh] is aiming for. To get an idea of that, snakeware also includes snakewm, a graphical user interface written with pygame that bundles a couple of simple applications as demonstration, including a terminal to execute Python one-liners.

Note that this is merely a proof of concept at this stage, but [Josh] is inviting everyone to contribute and extend his creation. If you want to give it a go without building the entire system, the GitHub repository has a prebuilt image to run in QEMU, and the window manager will run as regular Python application on your normal system, too. To get just a quick glimpse of it, check the demo video after the break.

Sure, die-hard Linux enthusiasts will hardly accept a distribution without their favorite shell and preferable language, but hey, at least it gets by without systemd. And while snakeware probably won’t compete with more established distributions in the near future, it’s certainly an interesting concept that embraces thinking outside the box and trying something different. It would definitely fit well on a business card.

Continue reading “Python Is All You’ll Ever Need In This Linux Distro” →