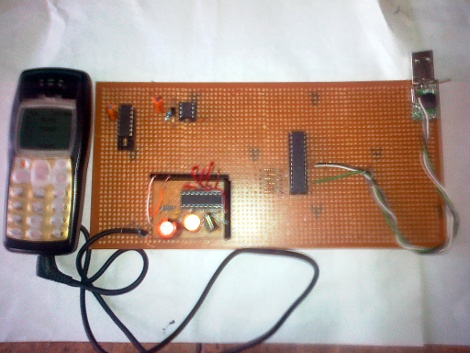

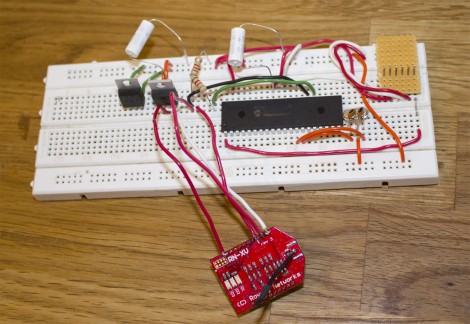

[Blaise Jarrett] has been grinding away to get the WebSocket protocol to play nicely with PIC microcontrollers. Here he’s using the PIC 18F4620 along with a Roving Networks RN-XV WiFi module to get the device on the network. He had started with a smaller processor but ran into some RAM restrictions so keep that in mind when choosing your hardware.

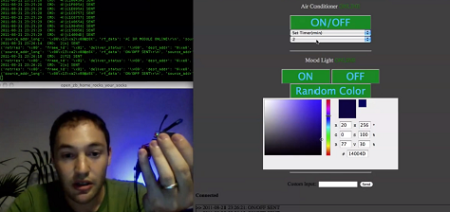

This project was spawned after seeing the mBed feature a few days back which combined that board along with a WebSocket library and HTML5 to pull off some pretty amazing stuff. [Blaise] doesn’t have quite as much polish on the web client yet, but he has recreated the data transfer method and improved on that project by moving to the newer version 13 of WebSockets. The protocol is kind of a moving target as it is still in the process of standardization.

The backend is a server called AutoBahn which is written in python. It comes along with client-side web server examples which gave him a chance to get up and running quickly. From there he got down to work with the WebSocket communications. They’re a set of strings that look very much like HTML headers. He outlines each command and some of the hangups one might run into with implementation. After reading what it takes to get this going it seems less complicated than we thought, but it’s obvious why you’ll need a healthy chunk of RAM to pull it off.