The original Xbox, released in 2001 by Microsoft, was notable for being built out of largely off-the-shelf PC components. With a custom Pentium III CPU and IDE peripherals, the console was much closer to a contemporary desktop computer than any of the dedicated game consoles which had come before it. Which of course makes perfect sense if you think about it. Microsoft would want to use technology they were intimately acquainted with on their first foray into gaming market, and if there’s anything Microsoft knows better than forced system updates, it’s x86 computers.

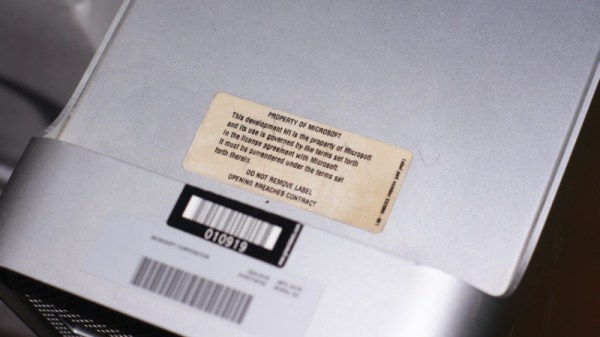

But for their follow-up system, the Xbox 360, Microsoft decided to go with a PowerPC processor they co-developed with IBM. Naturally this meant they needed PowerPC development systems to give to developers, which is how Microsoft ended up briefly distributing PowerMac G5’s. [Pierre Dandumont] came into possession of one of these oddball Microsoft-branded Macs, though unfortunately the hard drive had been wiped. But with the help of a leaked drive image and some hardware sleuthing, he’s now got the machine up and running just like it was when Microsoft was sending them to developers between 2003 and 2005.

Since you’re reading this on Hackaday, you might have guessed there was a little more to the story then just downloading an ISO and writing it to the hard drive of a PowerMac G5. There’s apparently some debate in the community about whether or not it’s some form of rudimentary DRM on Microsoft’s part, but in any event, the development kit operating system will only run on a G5 with very specific hardware. So the challenge is not only figuring out what hardware the software is looking for, but finding it and getting it installed over a decade after its prime.

Since you’re reading this on Hackaday, you might have guessed there was a little more to the story then just downloading an ISO and writing it to the hard drive of a PowerMac G5. There’s apparently some debate in the community about whether or not it’s some form of rudimentary DRM on Microsoft’s part, but in any event, the development kit operating system will only run on a G5 with very specific hardware. So the challenge is not only figuring out what hardware the software is looking for, but finding it and getting it installed over a decade after its prime.

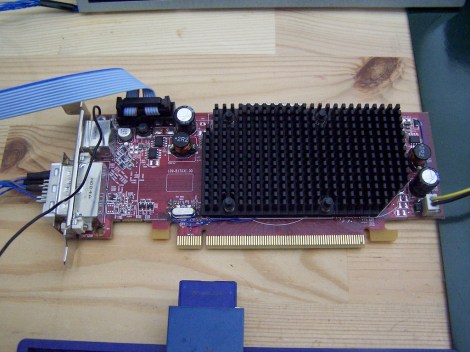

Most of the required hardware, like the Intel 741462-010 network card or 160 GB Seagate ST3160023AS hard drive were easy enough to track down on eBay. But the tricky one was finding a Mac version of the ATi Radeon X800 XT. [Pierre] ended up getting a much more common ATi FireGL X3 and flashing it with the Mac X800 firmware. This is a little easier said than done as depending on which manufacturer made the memory on your specific video card you have to fiddle with the clock speeds to get a usable image, but in the end he found the winning combination and the development kit OS booted up with his hacked graphics card.

So what does all this get you in 2019? [Pierre] admits nothing terribly useful, but it’s still pretty cool. The system lets you run Xbox and Xbox 360 binaries, and even features the old Xbox 360 “blade” style dashboard. He says that he’s only had limited success getting retail games to actually run on the thing, but if your goal was running Xbox 360 games in 2019 there’s certainly better ways to do that anyway. Like, buying an Xbox 360.

We’ve previously talked about the Xbox 360’s rather unusual processor, but around these parts we more often see projects which involve tearing Microsoft’s sophomore console apart than digging into how it actually worked.

Continue reading “The Mac That Helped Build The Xbox Rides Again” →