Begun, the Spectrum Wars have. First, it was AM radio getting the shaft (last item) and being yanked out of cars for the supposed impossibility of peaceful coexistence with rolling broadband EMI generators EVs. That battle has gone back and forth for the last year or two here in the US, with lawmakers even getting involved at one point (first item) by threatening legislation to make terrestrial AM radio available in every car sold. We’re honestly not sure where it stands now in the US, but now the Swiss seem to be entering the fray a little up the dial by turning off all their analog FM broadcasts at the end of the year. This doesn’t seem to be related to interference — after all, no static at all — but more from the standpoint of reclaiming spectrum that’s no longer turning a profit. There are apparently very few analog FM receivers in use in Switzerland anymore, with everyone having switched to DAB+ or streaming to get their music fix, and keeping FM transmitters on the air isn’t cheap, so the numbers are just stacked against the analog stations. It’s hard to say if this is a portent of things to come in other parts of the world, but it certainly doesn’t bode well for the overall health of terrestrial broadcasting. “First they came for AM radio, and I did nothing because I’m not old enough to listen to AM radio. But then they came for analog FM radio, and when I lost my album-oriented classic rock station, I realized that I’m actually old enough for AM.”

radio568 Articles

Hacking A Quansheng Handheld To Transmit Digital Modes

Have you ever thought about getting into digital modes on the ham bands? As it turns out, you can get involved using the affordable and popular Quansheng UV-K6 — if you’re game to modify it, that is. It’s perfectly achievable using the custom Mobilinkd firmware, the brainchild of one [Rob Riggs].

In order to efficiently transmit digital modes, it’s necessary to make some hardware changes as well. Low frequencies must be allowed to pass in through the MIC input, and to pass out through the audio output. These are normally filtered out for efficient transmission of speech, but these filters mess up digital transmissions something fierce. This is achieved by messing about with some capacitors and bodge wires. Then, one can flash the firmware using a programming cable.

With the mods achieved, the UV-K6 can be used for transmitting in various digital modes, like M17 4-FSK. The firmware has several benefits, not least of which is cutting turnaround time. This is the time the radio takes to switch between transmitting and receiving, and slashing it is a big boost for achieving efficient digital communication. While the stock firmware has an excruciating slow turnaround of 378 ms, the Mobilinkd firmware takes just 79 ms.

Further gains may be possible in future, too. Bypassing the audio amplifier could be particularly fruitful, as it’s largely in the way of the digital signal stream.

Quansheng’s radios are popular targets for modification, and are well documented at this point.

So Much Going On In So Few Components: Dissecting A Microwave Radar Module

In the days before integrated circuits became ubiquitous, providing advanced functionality in a single package, designers became adept at extracting the maximum use from discrete components. They’d use clever circuits in which a transistor or other active part would fulfill multiple roles at once, and often such circuits would need more than a little know-how to get working. It’s not often in 2024 that we encounter this style of circuit, but here’s [Maurycy] with a cheap microwave radar module doing just that.

Continue reading “So Much Going On In So Few Components: Dissecting A Microwave Radar Module”

Learning Morse Code With A DIY Trainer

Morse code, often referred to as continuous wave (CW) in radio circles, has been gradually falling out of use for a long time now. At least in the United States, ham radio licensees don’t have to learn it anymore, and the US Coast Guard stopped using it even for emergencies in 1999. It does have few niche use cases, though, as it requires an extremely narrow bandwidth and a low amount of power to get a signal out and a human operator can usually distinguish it even if the signal is very close to the noise floor. So if you want to try and learn it, you might want to try something like this Morse trainer from [mircemk].

While learning CW can be quite tedious, as [mircemk] puts it, it’s actually fairly easy for a computer to understand and translate so not a lot of specialized equipment is needed. This build is based around the Arduino Nano which is more than up for the job. It can accept input from any audio source, allowing it to translate radio transmissions in real time, and can also be connected to a paddle or key to be used as a trainer for learning the code. It’s also able to count the words-per-minute rate of whatever it hears and display it on a small LCD at the front of the unit which also handles displaying the translations of the Morse code.

If you need a trainer that’s more compact for on-the-go CW, though, take a look at this wearable Morse code device based on the M5StickC Plus instead.

Hackaday Links: June 9, 2024

We’ve been harping a lot lately about the effort by carmakers to kill off AM radio, ostensibly because making EVs that don’t emit enough electromagnetic interference to swamp broadcast signals is a practical impossibility. In the US, push-back from lawmakers — no doubt spurred by radio industry lobbyists — has put the brakes on the move a bit, on the understandable grounds that an entire emergency communication system largely centered around AM radio has been in place for the last seven decades or so. Not so in Japan, though, as thirteen of the nation’s 47 broadcasters have voluntarily shut down their AM transmitters in what’s billed as an “impact study” by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. The request for the study actually came from the broadcasters, with one being quoted in a hearing on the matter as “hop[ing] that AM broadcasting will be promptly discontinued.” So the writing is apparently on the wall for AM radio in Japan.

Grid Leak Radio Draws The Waves

[Stephen McNamera] found a schematic for a grid leak radio online and decided to throw together a few tubes on a piece of wood and see how it worked. As you can see in the video below, it works well. The video is a bit light on details, but the web page he found the plans on also has quite a bit of explanation.

The name “grid leak detector” is due to the grid leak resistor between the grid and ground, in this case, a 2.7 megaohm resistor. The first tube does everything, including AM detection. The second tube is just an audio amplifier that drives the speaker. This demodulation method relies on the cathode to control grid conduction characteristics and was found in radios up to about the 1930s. The control grid performs the usual function but also acts as a diode with the cathode, providing demodulation. In a way, this is similar to a crystal radio but with an amplified tube diode instead of a crystal.

It looks like [Stephen] wound his own coil, and the variable capacitor looks suspiciously like it may have come from an old AM radio. The of the old screw terminal tube sockets on the wood board looks great. Breadboard indeed! What we didn’t see is where the 150 V plate voltage comes from. You hope there is a transformer somewhere and some filter capacitors. Or, perhaps he has a high-voltage supply on the bench.

While tubes are technologically passe, we still like them. Especially in old radios. Just take care around the high voltages, please.

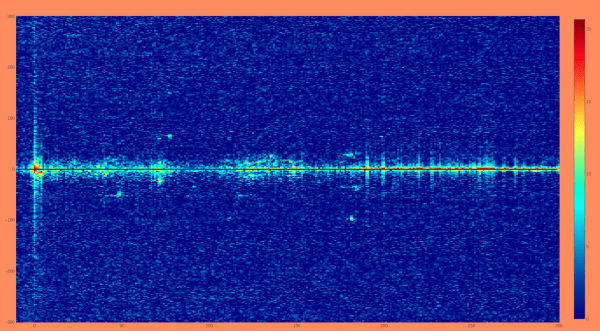

DIY Passive Radar System Verifies ADS-B Transmissions

Like most waves in the electromagnetic spectrum, radio waves tend to bounce off of various objects. This can be frustrating to anyone trying to use something like a GMRS or LoRa radio in a dense city, for example, but these reflections can also be exploited for productive use as well, most famously by radar. Radar has plenty of applications such as weather forecasting and various military uses. With some software-defined radio tools, it’s also possible to use radar for tracking aircraft in real-time at home like this DIY radar system.

Unlike active radar systems which use a specific radio source to look for reflections, this system is a passive radar system that uses radio waves already present in the environment to track objects. A reference antenna is used to listen to the target frequency, and in this installation, a nine-element Yagi antenna is configured to listen for reflections. The radio waves that each antenna hears are sent through a computer program that compares the two to identify the reflections of the reference radio signal heard by the Yagi.

Even though a system like this doesn’t include any high-powered active elements, it still takes a considerable chunk of computing resources and some skill to identify the data presented by the software. [Nathan] aka [30hours] gives a fairly thorough overview of the system which can even recognize helicopters from other types of aircraft, and also uses the ADS-B monitoring system as a sanity check. Radar can be used to monitor other vehicles as well, like this 24 GHz radar module found in some modern passenger vehicles.

Continue reading “DIY Passive Radar System Verifies ADS-B Transmissions”