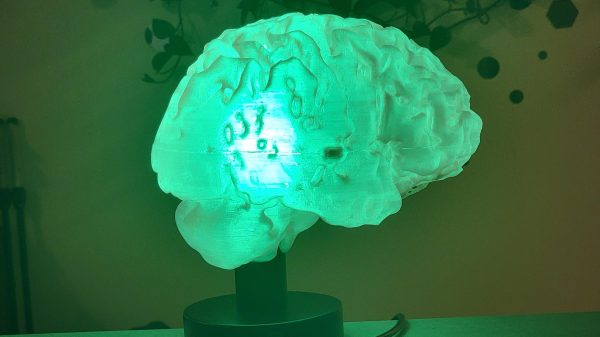

MRIs generally fall somewhere on the scale from boring to stressful depending on why you’re having one and how claustrophobic you get. Regardless, they’re a wonderful diagnostic tool and they’ve saved thousands if not millions of lives over the years. In a fun use of the technology, [mandalaFractals] has shown us how to make a 3D-printed brain lamp using an MRI scan of the head.

The build starts with an off-the-shelf lamp base and a smart LED bulb as the light source, though you could swap those out as desired for something like a microcontroller, a USB power supply, and addressable LEDs if you were so inclined. The software package Slicer is then used to take an MRI brain scan and turn it into something that you can actually 3D print. It’ll take some cleaning up to remove artifacts and hollow it out, but it’s straightforward enough to get a decent brain model out of the data. Alternatively, you can use someone else’s if you don’t have your own scan. Then, all you have to do is print it in a couple of halves, and pop it on the lamp base, and you’re done!

It’s a pretty neat build. Who wouldn’t love telling their friends that their new brain lamp was an accurate representation of their own grey noodles, after all? It could be a fun gift next time Halloween rolls around, too!

Meanwhile, if you’ve got your own MRI hacks that you’ve been cooking up, don’t hesitate to let us know!