In Europe, the GRAVES radar station beams a signal on 143.050 MHz almost straight up to detect and track satellites and space junk. That means you will generally not hear any signal from the station. However, [DK8OK] shows how you can–if you are in Europe–listen for reflections from the powerful radar. The reflections can come from airplanes, meteors, or spacecraft. You can see a video from [way1888] showing the result of the recent Perseid meteor shower.

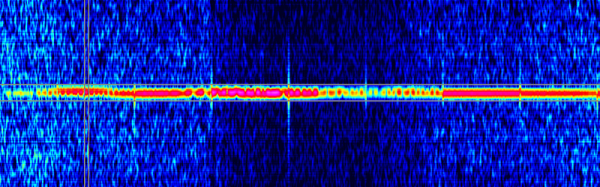

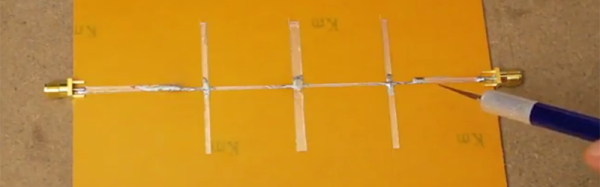

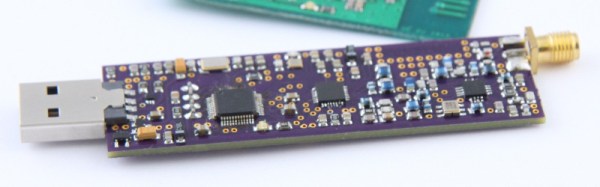

Using a software-defined radio receiver, [DK8OK] tunes slightly off frequency and waits for reflections to appear in the waterfall. In addition to observing the signal, it is possible to process the audio to create more details.

Why is there a giant vertical radar transmitter in the middle of France? The transmitter uses a phased array to send a signal over a 45-degree swath of the sky at a time. It makes six total steps every 19.2 seconds. A receiver several hundred miles away listens for reflections.

Even the moon reflects the signal when it is in the radar’s path. If you are interested in a moon bounce, you may be able to build a station to hear the reflections without being in Europe.

Of course, if you can transmit yourself, you might want to bounce your own signal off airplanes. If you want to do it old school, you could emulate [Zoltán Bay].

Continue reading “Sorry US; Europeans Listen To Space With GRAVES”