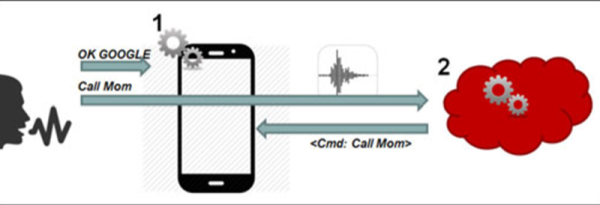

Last week saw the revelation that you can control Siri and Google Now from a distance, using high power transmitters and software defined radios. Is this a risk? No, it’s security theatre, the fine art of performing an impractical technical achievement while disclosing these technical vulnerabilities to the media to pad a CV. Like most security vulnerabilities it is very, very cool and enough details have surfaced that this build can be replicated.

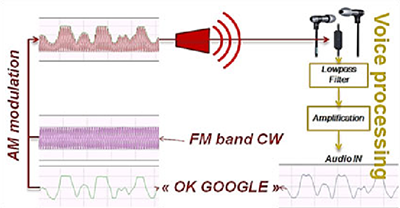

The original research paper, published by researchers [Chaouki Kasmi] and [Jose Lopes Esteves] attacks the latest and greatest thing to come to smartphones, voice commands. iPhones and Androids and Windows Phones come with Siri and Google Now and Cortana, and all of these voice services can place phone calls, post something to social media, or launch an application. The trick to this hack is sending audio to the microphone without being heard.

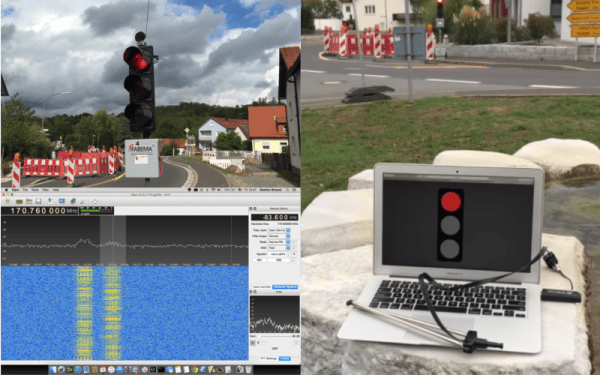

The ubiquitous Apple earbuds have a single wire for a microphone input, and this is the attack vector used by the researchers. With a 50 Watt VHF power amplifier (available for under $100, if you know where to look), a software defined radio with Tx capability ($300), and a highly directional antenna (free clothes hangers with your dry cleaning), a specially crafted radio message can be transmitted to the headphone wire, picked up through the audio in of the phone, and understood by Siri, Cortana, or Google Now.

The ubiquitous Apple earbuds have a single wire for a microphone input, and this is the attack vector used by the researchers. With a 50 Watt VHF power amplifier (available for under $100, if you know where to look), a software defined radio with Tx capability ($300), and a highly directional antenna (free clothes hangers with your dry cleaning), a specially crafted radio message can be transmitted to the headphone wire, picked up through the audio in of the phone, and understood by Siri, Cortana, or Google Now.

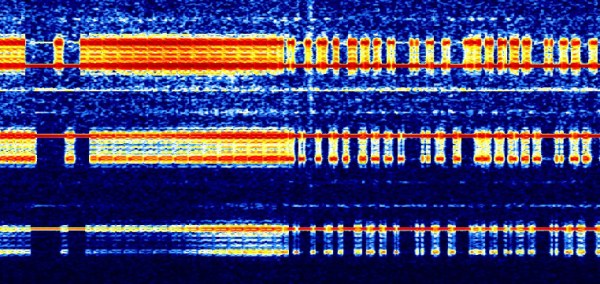

There is of course a difference between a security vulnerability and a practical and safe security vulnerability. Yes, for under $400 and the right know-how, anyone could perform this technological feat on any cell phone. This feat comes at the cost of discovery; because of the way the earbud cable is arranged, the most efficient frequency varies between 80 and 108 MHz. This means a successful attack would sweep through the band at various frequencies; not exactly precision work. The power required for this attack is also intense – about 25-30 V/m, about the limit for human safety. But in the world of security theatre, someone with a backpack, carrying around a long Yagi antenna, pointing it at people, and having FM radios cut out is expected.

Of course, the countermeasures to this attack are simple: don’t use Siri or Google Now. Leaving Siri enabled on a lock screen is a security risk, and most Androids disable Google Now on the lock screen by default. Of course, any decent set of headphones would have shielding in the cable, making inducing a current in the microphone wire even harder. The researchers are at the limits of what is acceptable for human safety with the stock Apple earbuds. Anything more would be seriously, seriously dumb.

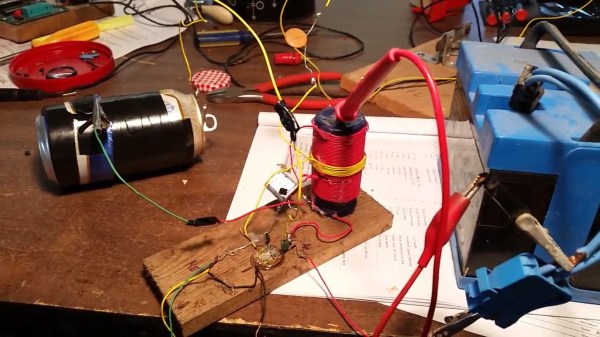

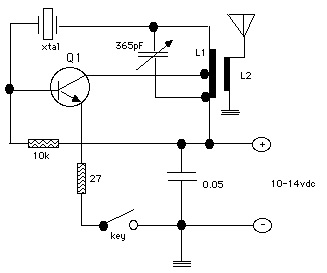

If the crystal is “easily” scavengeable, and the rest of the radio is easily home-made, the tuning capacitor (obtainable from old AM/FM radios) can become the sticking point. So [Paul] cut up two aluminum “beverage” cans, wrapped the inner one in electrical tape, hooked up wires and made his own variable capacitor. By sliding the cans in or out so that more or less of them overlap, he can tune the radio to exactly the crystal’s natural frequency.

If the crystal is “easily” scavengeable, and the rest of the radio is easily home-made, the tuning capacitor (obtainable from old AM/FM radios) can become the sticking point. So [Paul] cut up two aluminum “beverage” cans, wrapped the inner one in electrical tape, hooked up wires and made his own variable capacitor. By sliding the cans in or out so that more or less of them overlap, he can tune the radio to exactly the crystal’s natural frequency.