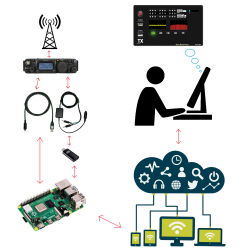

It’s a common scene: a dedicated radio amateur wakes up early in the morning, ambles over to their shack, and sits in the glow of vacuum tubes as they call CQ DX, trying to contact hams in time zones across the world. It’s also a common scene for the same ham to sit in the comfort of their living room, sipping hot chocolate and  remote-controlling their rig from a laptop. As you can imagine, this essentially involves a server running on a computer hooked up to the radio, which is connected via the internet to a client running on the laptop. [Olivier/ F4HTB] saw a way to improve the process by eliminating the client software and controlling the rig from a web browser.

remote-controlling their rig from a laptop. As you can imagine, this essentially involves a server running on a computer hooked up to the radio, which is connected via the internet to a client running on the laptop. [Olivier/ F4HTB] saw a way to improve the process by eliminating the client software and controlling the rig from a web browser.

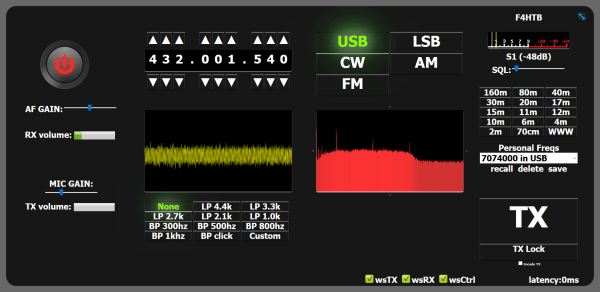

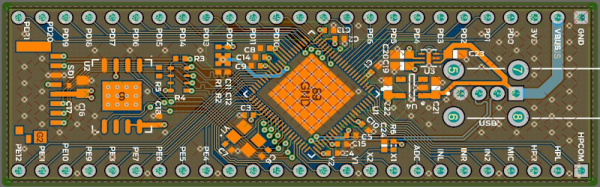

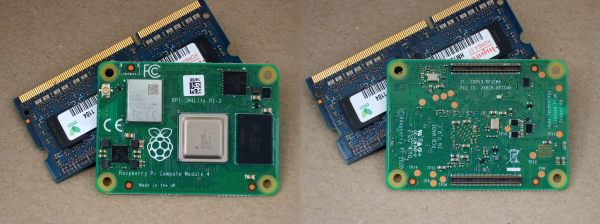

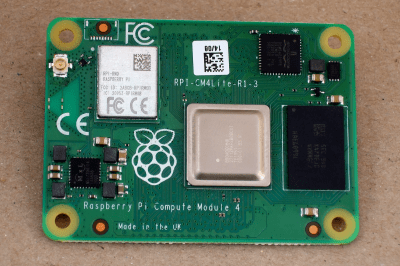

[Oliver]’s software, aptly named Universal HamRadio Remote, runs a web server that hosts an HTML5 dashboard for controlling the radio. It also pipes audio back and forth (radio control wouldn’t be very useful if you couldn’t talk!), and can be run on a Raspberry Pi. Not only does this make setup easier, as there is no need to configure the client machine, but it also makes the radio accessible from nearly any modern device.

We’ve seen a similar (albeit expensive and closed-source) solution, the MFJ-1234, before, but it’s always refreshing to see the open-source community tackle a problem and make it their own. We can’t wait to see where the project goes next!