A solar eclipse is coming up in just a few weeks, and although with its path of totality near the southern tip of South America means that not many people will be able to see it first-hand, there is an opportunity to get involved with it even at an extreme distance. PhD candidate [Kristina] and the organization HamSCI are trying to learn a little bit more about the effects of an eclipse on radio communications, and all that is required to help is a receiver capable of listening in the 10 MHz range during the time of the eclipse.

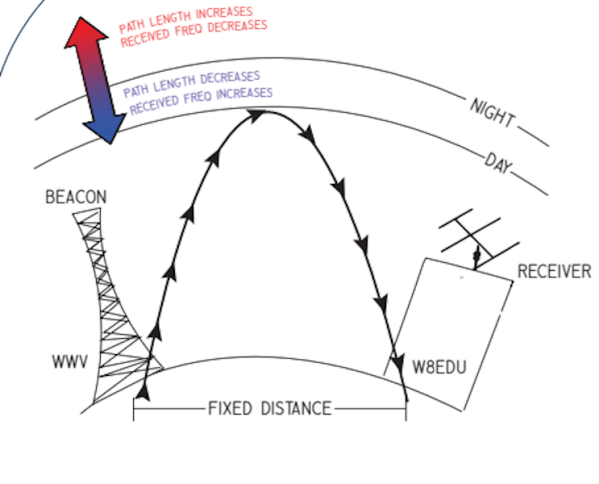

It’s well-known that certain radio waves can propagate further depending on the time of day due to changes in many factors such as the state of the ionosphere and the amount of solar activity. What is not known is specifically how the paths can vary over the course of the day. During the eclipse the sun’s interference is minimized, and its impact can be more directly measured in a more controlled experiment. By tuning into particular time stations and recording data during the eclipse, it’s possible to see how exactly the eclipse impacts propagation of these signals. [Kristina] hopes to take all of the data gathered during the event to observe the doppler effect that is expected to occur.

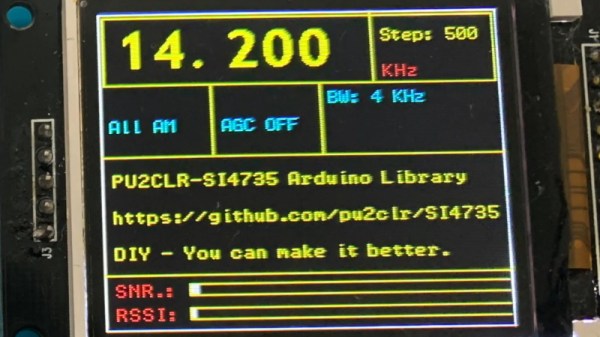

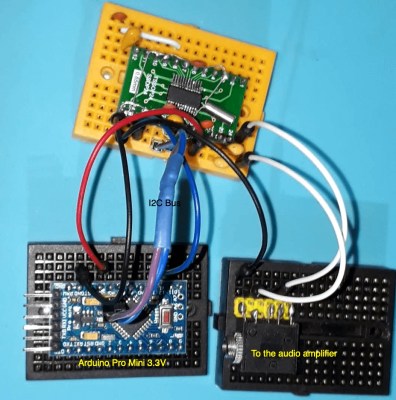

The project requires a large amount of volunteers to listen in to the time stations during the eclipse (even if it is not visible to them) and there are only a few more days before this eclipse happens. If you have the required hardware, which is essentially just a receiver capable of receiving upper-sideband signals in 10 MHz range, it may be worthwhile to give this a shot. If not, there may be some time to cobble together an SDR that can listen in (even an RTL-SDR set up for 10 MHz will work) provided you can use it to record the required samples. It’s definitely a time that ham radio could embrace the hacker community.

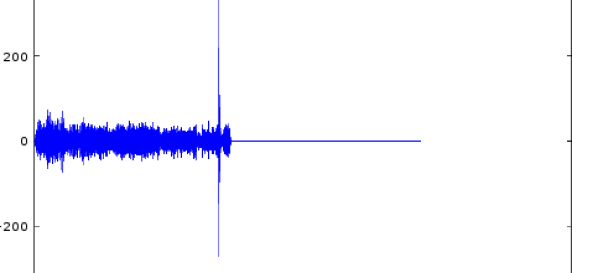

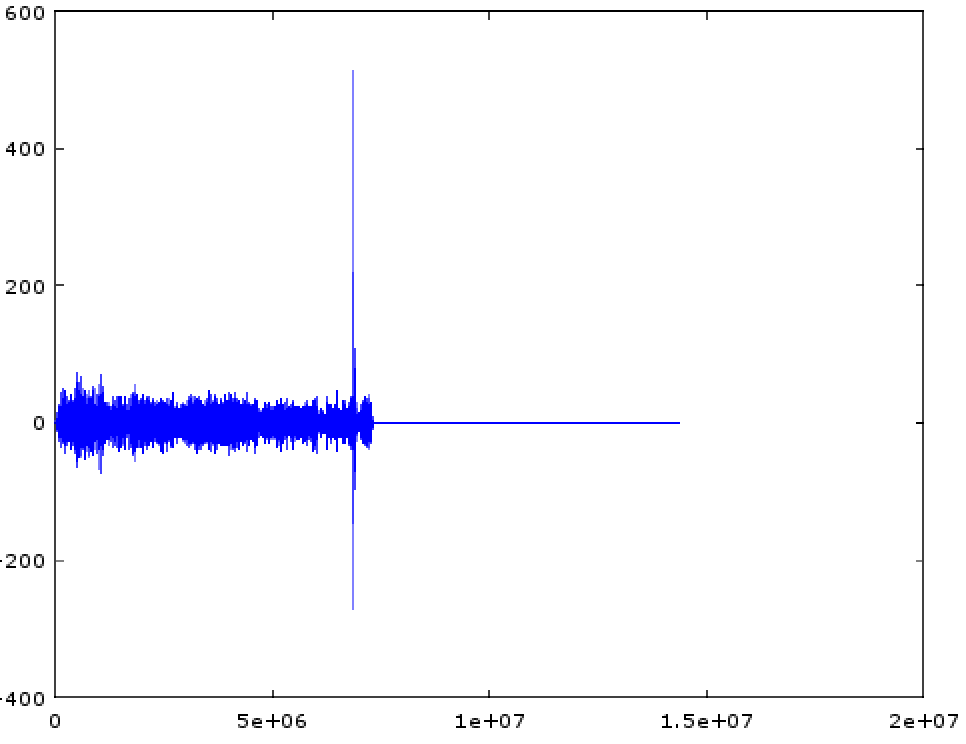

[tomek] was aware of this hip knowledge domain called Digital Signal Processing but hadn’t done any of it themselves. Like many algorithmic problems the first step was to figure out the fastest way to bolt together a prototype to prove a given technique worked. We were as surprised as [tomek] by how simple this turned out to be. Fundamentally it required a single function – cross-correlation – to measure the similarity of two data samples (audio files in this case). And it turns out that

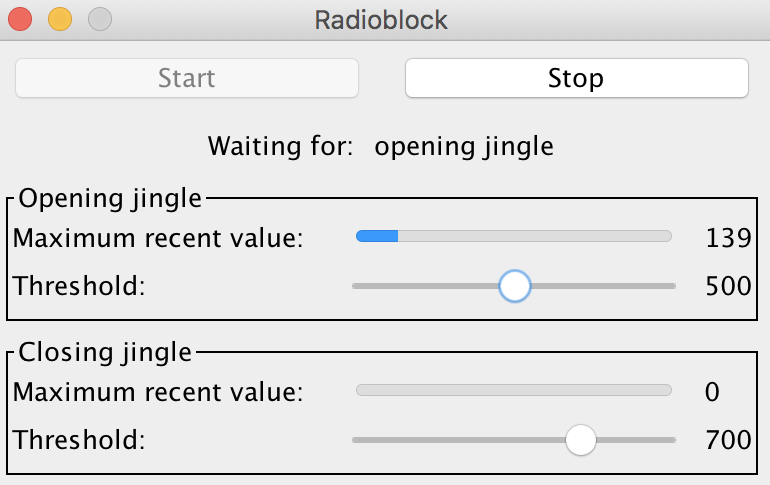

[tomek] was aware of this hip knowledge domain called Digital Signal Processing but hadn’t done any of it themselves. Like many algorithmic problems the first step was to figure out the fastest way to bolt together a prototype to prove a given technique worked. We were as surprised as [tomek] by how simple this turned out to be. Fundamentally it required a single function – cross-correlation – to measure the similarity of two data samples (audio files in this case). And it turns out that  At this point all that was left was packaging it all into a one click tool to listen to the radio without loading an entire analysis package. Conveniently Octave is open source software, so [tomek] was able to dig through its sources until they found the bones of the critical xcorr() function. [tomek] adapted their code to pour the audio into a circular buffer in order to use an existing Java FFT library, and the magic was done. Piping the stream out of ffmpeg and into the ad detector yielded events when the given ad jingle samples were detected.

At this point all that was left was packaging it all into a one click tool to listen to the radio without loading an entire analysis package. Conveniently Octave is open source software, so [tomek] was able to dig through its sources until they found the bones of the critical xcorr() function. [tomek] adapted their code to pour the audio into a circular buffer in order to use an existing Java FFT library, and the magic was done. Piping the stream out of ffmpeg and into the ad detector yielded events when the given ad jingle samples were detected.