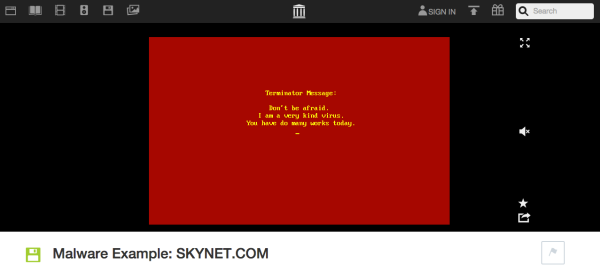

There’s some debate on which program gets the infamous title of “First Computer Virus”. There were a few for MS-DOS machines in the 80s and even one that spread through ARPANET in the 70s. Even John von Neumann theorized that programs might one day self-replicate. To compile all of these early examples of malware, and possibly settle this question once and for all, [Mikko Hypponen] has started collecting many of the early malware programs into a Museum of Malware.

While unlucky (or careless) users today are confronted with entire hard drive encryption viruses (or worse), a lot of the early viruses were relatively harmless. Examples include Brain which spread via floppy disk, the experimental ARPANET virus, or Elk Cloner which, despite many geniuses falsely claiming that Apples are immune to viruses, infected Mac computers of the 80s. [Mikko] has collected many more from this era that can be downloaded or demonstrated in a browser.

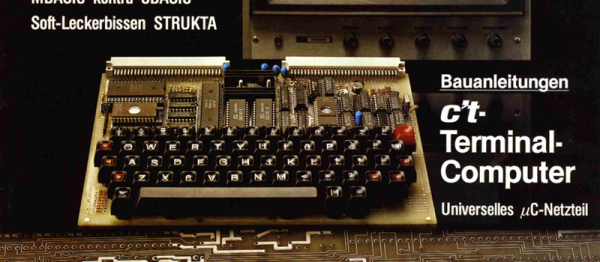

Retrocomputing is an active community, with users keeping gear of this era up and running despite it being 30+ years old. This software, while malicious at the time, is a great look into what the personal computing world was like in its infancy. And don’t forget, if you have a beige computer from a bygone era, you can always load up our Retro Page.

Thanks to [chad] for the tip!