If someone in 2023 has ever had much call to use turpentine, chances are good it was something to do with paint or other wood finishes, like varnish. Natural turpentine is the traditional solvent of choice for oil paints, which have decreased in popularity with the rise of easy-to-clean polymer-based paints and coating. Oh sure, there are still those who prefer oil paint, especially for trim work — it lays up so nice — but by and large, turpentine seems like a relic from days gone by, like goose grease and castor oil.

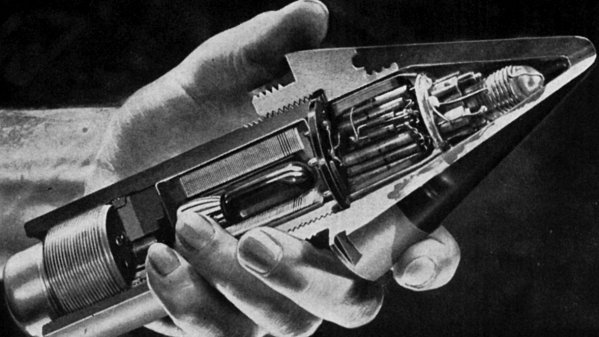

It wasn’t always so, though. Turpentine used to be a very big deal indeed, as shown by this circa 1940 documentary on the turpentine harvesting and processing industry. Even then it was only a shadow of its former glory, when it was a vital part of a globe-spanning naval empire and a material of the utmost strategic importance. “Suwanee Pine” shows the methods used in the southern United States, where fast-growing pines offer up a resinous organic gloop in response to wounds in their bark. The process shown looks a lot like the harvesting process for natural latex, with slanting gashes or “catfaces” carved into the trunks of young trees, forming channels to guide the exudate down into a clay collecting cup.

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: The Story Of Turpentine”