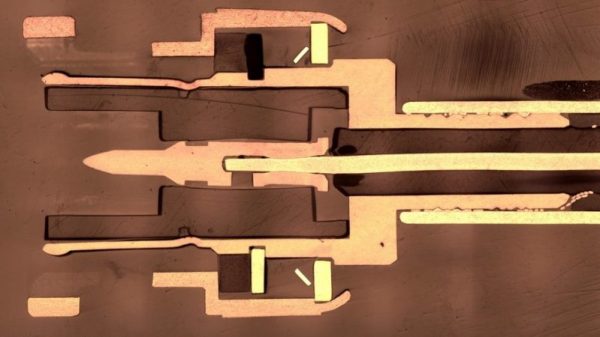

While browsing through an antiques shop, [Nick Morganti] came across a Kodak slide projector with an absolutely massive lens hanging off the front. Nearly a foot long and with a front diameter of approximately four inches, the German-made ISCO optic was a steal for just $10. The only tricky part was figuring out how to use it on a modern DSLR camera.

After liberating the lens from the projector, [Nick] noted the rear seemed to be nearly the same diameter as the threaded M42 mount that was popular with older film cameras. As luck would have it, he already had an adapter that let him use an old Soviet M42 lens on his camera. The thread pitch didn’t match at all, but by holding the lens up to the adapter he was able to experiment a bit with the focus and take some test shots.

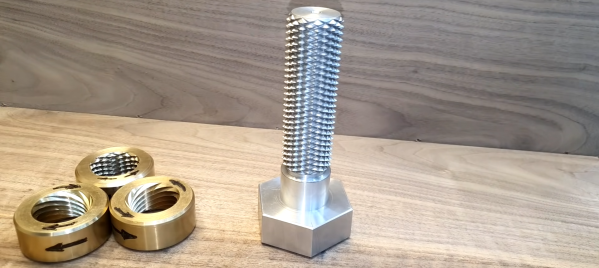

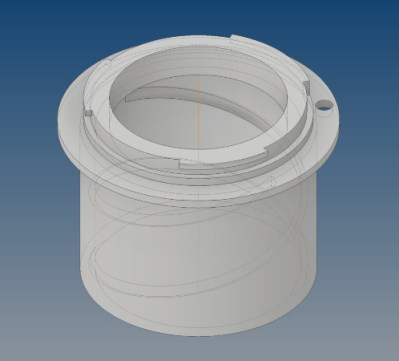

Encouraged by these early tests, [Nick] went about designing a 3D printed adapter. His first attempt was little more than a pair of concentric cylinders, and was focused like an old handheld spyglass. This worked, but it was quite finicky to use with the already ungainly lens. His second attempt added internal threads to the mix, which allowed him to more easily control focus. After he was satisfied with the design, he glued a small ring over the adapter so the lens could no longer be unscrewed all the way and accidentally fall out.

Encouraged by these early tests, [Nick] went about designing a 3D printed adapter. His first attempt was little more than a pair of concentric cylinders, and was focused like an old handheld spyglass. This worked, but it was quite finicky to use with the already ungainly lens. His second attempt added internal threads to the mix, which allowed him to more easily control focus. After he was satisfied with the design, he glued a small ring over the adapter so the lens could no longer be unscrewed all the way and accidentally fall out.

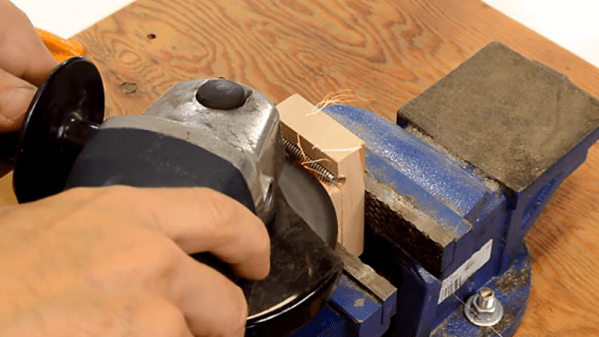

To us, this project is a perfect application of desktop 3D printing.[Nick] was able to conceptualize a one-of-a-kind design, test it, iterate on it, and arrive on a finished product, all without having to leave the comfort of his own home. To say nothing of the complex design of the adapter, which would be exceedingly difficult to produce via traditional means. Perhaps some people’s idea of a good time is trying to whittle a lens bayonet out of wood, but it certainly isn’t ours.

So it’s probably little surprise we’ve seen a number of similar projects over the years. From monstrous anamorphic adapters to upgraded optics for the Game Boy Camera, it seems there’s a healthy overlap between the 3D printing and photography communities.