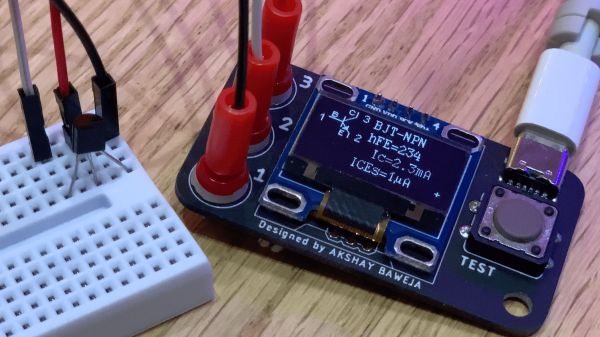

We like to pretend that our circuit elements are perfect because, honestly, it makes life easier and it often doesn’t matter much in practice. For a normal design, the fact that a foot of wire has a tiny bit of resistance or that our capacitor value might be off by 10% doesn’t make much difference. One place that we really bury our heads in the sand, though, is when we use bipolar transistors as switches. A perfect switch would have 0 volts across it when it is actuated. A real switch won’t quite get there, but it will be doggone close. But a bipolar transistor in saturation won’t be really all the way on. [The Offset Volt] looks at how a bipolar transistor switches and why the voltage across it at saturation is a few tenths of a volt. You can see the video below.

To understand it, you’ll need a little bit of math and some understanding of the construction of transistors. The idea of using a transistor as a switch is that the transistor is saturated — that is, increasing base current doesn’t make much change in the collector current. While it isn’t perfect, it is good enough to switch a relay or do other common switching tasks.