[M Caldeira] had a project in mind: replacing a common vacuum tube with a solid-state equivalent. The tube in question was an EABC80 or 6AK8 triple diode triode. The key was identifying a high-voltage FET and building it, along with some other components, into a tube base to make a plug-in replacement for the tube. You can see a video about the project below.

These tubes are often used as a detector and preamplifier. Removing the detector tube from a working radio, of course, kills the audio. Replacing the tube with a single diode restores the operation of the radio, although at a disadvantage.

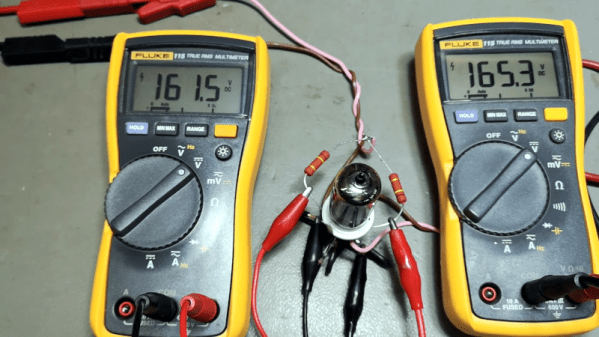

From there, he adds more diodes directly into the socket. Of course, diodes don’t amplify, so he had to break out a LND150 MOSFET with a limit of 500 volts across the device. It takes some additional components, and the whole thing fits in a tube base ready for the socket.

Usually, we see people go the other way using tubes instead of transistors in, say, a computer. If you want real hacking, why not make your own tubes?