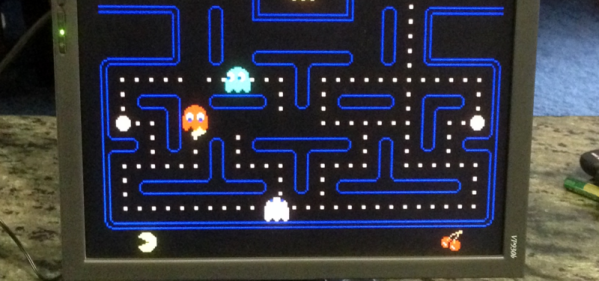

We really love when hacks of previous hacks show up in the tip line. It shows how the hardware hacking community can be a feedback loop, where one hack begets the next, and so on until great things are everywhere. This hacked joystick port for an FPGA Pac Man game is a perfect example of that creative churn.

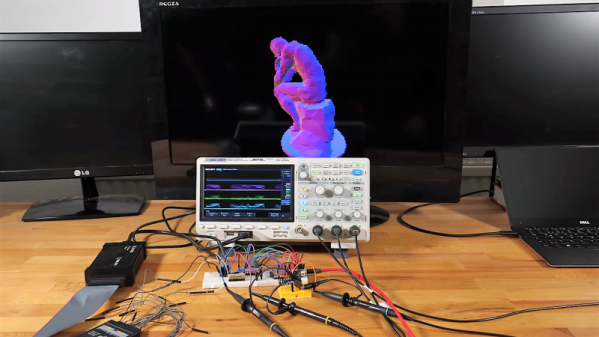

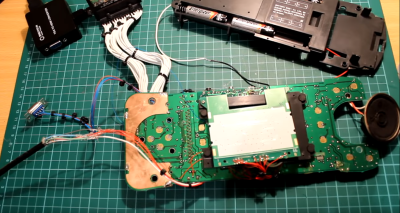

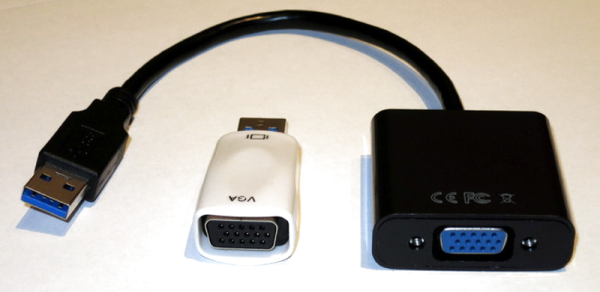

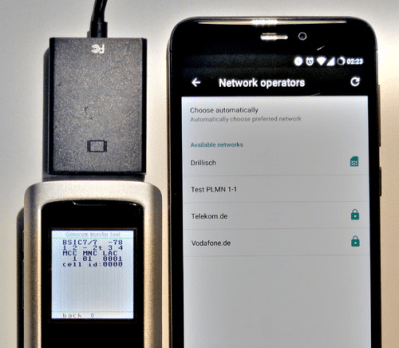

The story starts with Pano Man, a version of the venerable arcade game ported to a Pano Logic FPGA thin client by [Skip]. We covered that story when it first came out, and it caught the attention of [Tom Verbeure], particularly the bit in the GitHub readme file which suggested there might be a better way to handle the joystick connections. So [Tom] took up the challenge of using the Extended Display Identification Data (EDID) circuit in the VGA connector to support an Atari 2600 joystick. The EDID system is an I²C bus, so the job needed the right port expander. [Tom] chose the MCP23017, a 16-bit device that would have enough GPIO for dual joysticks and a few extra buttons. Having never designed a PCB before, [Tom] fell down that rabbit hole for a bit, but quickly came up with a working design, and then a better one, and then the final version. The video below shows it in action with Pano Man.

We think the creative loop between [Skip] and [Tom] was great here, and we can’t wait to see who escalates next. And it’s pretty amazing how much IO can be stuffed over two wires if you have the right tools. Check out this VGA sniffing effort to learn more about EDID and I²C.

Continue reading “Two Joysticks Talk To FPGA Arcade Game Over A VGA Cable”