If you were to nominate a technology from the 19th century that most defined it and which had the greatest effect in shaping it, you might well settle upon the railway. Over the century what had started as horse-drawn mining tramways evolved into a global network of high-speed transport that meant travel times to almost anywhere in the world on land shrank from months or weeks to days or hours.

For Brits, by the end of the century a comprehensive network connected almost all but the very smallest towns and villages. There had been many railway companies formed over the years to build railways of all sizes, but these had largely conglomerated into a series of competing companies with a regional focus. Each one had its own main line, all of which radiated out from London to the regions like the spokes of a wheel.

By the 1890s there was only one large and ambitious railway company left that had not built a London main line. The Great Central Railway’s heartlands lay in the North Midlands and the North of England, yet had never extended southwards. In the 1890s they launched their ambitious scheme to build their London connection, an entirely new line from their existing Nottingham station to a new terminus at Marylebone, in London.

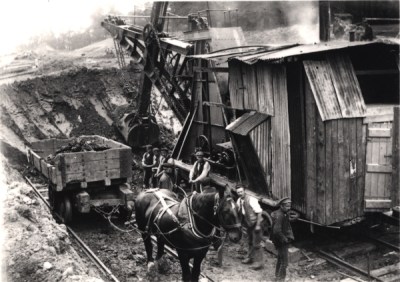

Since this was the last of the great British main lines, and built many decades after its rivals, it saw the benefit of the century’s technological advancement. Gone were the thousands of navvies (construction workers, from “Navigational”) digging and moving soil and rock by hand, and in their place the excavation was performed using the latest steam shovels. The latest standards were used in its design, too, with shallow curves and gradients, no level crossings, and a wider Continental loading gauge in anticipation of a future channel tunnel to France This was a high-speed railway built sixty years before modern high-speed trains, and nearly ninety years before the Channel Tunnel was opened.

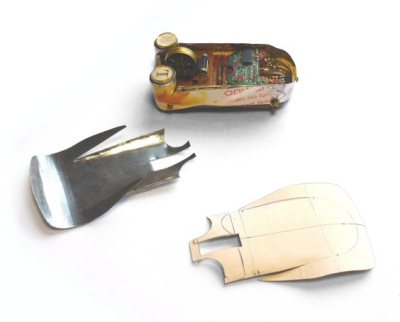

We were afraid the project would require advanced wood or metal working capability, but the bottom of the mouse is made from paper mache. The top and sides are cut from tinplate. Of course, the paint job is everything.

We were afraid the project would require advanced wood or metal working capability, but the bottom of the mouse is made from paper mache. The top and sides are cut from tinplate. Of course, the paint job is everything.

We understand where [John Clarke Mills] is coming from when he says he wants a home theater but not at the expense of dedicating a room to it. His situation is a bit more sticky than most folks in that he has a beautifully kept Victorian era home. Recently he was removing a renovation from ages past that didn’t fit with the style and it gave him the opportunity to

We understand where [John Clarke Mills] is coming from when he says he wants a home theater but not at the expense of dedicating a room to it. His situation is a bit more sticky than most folks in that he has a beautifully kept Victorian era home. Recently he was removing a renovation from ages past that didn’t fit with the style and it gave him the opportunity to