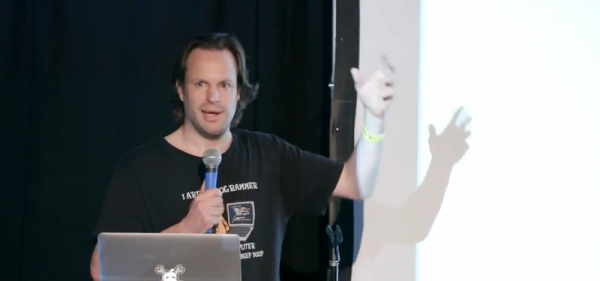

Nobody likes opening up a hacking target and finding a black epoxy blob inside, but all hope is not lost. At least not if you’ve got the dedication and skills of [Jeroen Domburg] alias [Sprite_tm].

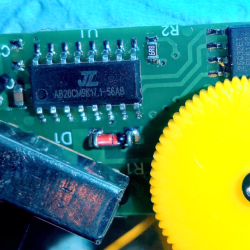

It all started when [Big Clive] ordered a chintzy Chinese musical meditation flower and found a black blob. But tantalizingly, the shiny plastic mess also included a 2 MB flash EEPROM. The questions then is: can one replace the contents with your own music? Spoiler: yes, you can! [Sprite_tm] and a team of Buddha Chip Hackers distributed across the globe got to work. (Slides here.)

It all started when [Big Clive] ordered a chintzy Chinese musical meditation flower and found a black blob. But tantalizingly, the shiny plastic mess also included a 2 MB flash EEPROM. The questions then is: can one replace the contents with your own music? Spoiler: yes, you can! [Sprite_tm] and a team of Buddha Chip Hackers distributed across the globe got to work. (Slides here.)

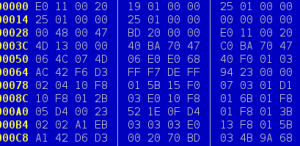

[Jeroen] started off with binwalk and gets, well, not much. The data that [Big Clive] dumped had high enough entropy that it looks either random or encrypted, with the exception of a couple tiny sections. Taking a look at the data, there was some structure, though. [Jeroen] smelled shitty encryption. Now in principle, there are millions of bad encryption methods out there for every good one. But in practice, naive cryptographers tend to gravitate to a handful of bad patterns.

Bad pattern number one is XOR. Used correctly, XORing can be a force for good, but if you XOR your key with zeros, naturally, you get the key back as your ciphertext. And this data had a lot of zeros in it. That means that there were many long strings that started out the same, but they seemed to go on forever, as if they were pseudo-random. Bad crypto pattern number two is using a linear-feedback shift register for your pseudo-random numbers, because the parameter space is small enough that [Sprite_tm] could just brute-force it. At the end, he points out their third mistake — making the encryption so fun to hack on that it kept him motivated!

Bad pattern number one is XOR. Used correctly, XORing can be a force for good, but if you XOR your key with zeros, naturally, you get the key back as your ciphertext. And this data had a lot of zeros in it. That means that there were many long strings that started out the same, but they seemed to go on forever, as if they were pseudo-random. Bad crypto pattern number two is using a linear-feedback shift register for your pseudo-random numbers, because the parameter space is small enough that [Sprite_tm] could just brute-force it. At the end, he points out their third mistake — making the encryption so fun to hack on that it kept him motivated!

Decrypted, the EEPROM data was a filesystem. And the machine language turned out to be for an 8051, but there was still the issue of the code resident on the microcontroller’s ROM. So [Sprite_tm] bought one of these flowers, and started probing around the black blob itself. He wrote a dumper program that output the internal ROM’s contents over SPI. Ghidra did some good disassembling, and that let him figure out how the memory was laid out, and how the flow worked. He also discovered a “secret” ROM area in the chip’s flash, which he got by trying some random functions and looking for side effects. The first hit turned out to be a memcpy. Sweet.

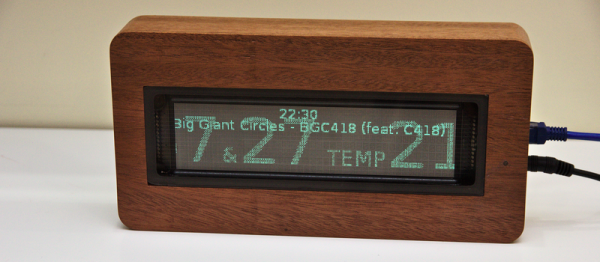

Well, victory if all you wanted to do was hack your music onto the chip. As a last final fillip, [Sprite_tm] mashed the reverse-engineered schematic of the Buddha Flower together with [Thomas Flummer]’s very nice DIY Remoticon badge, and uploaded our very own intro theme music into the device on a badge. Bonus points? He added LEDs that blinked out the LSFR that were responsible for the “encryption”. Sick burn!

Editor’s Note: This is the last of the Remoticon 2 videos we’ve got. Thanks to all who gave presentations, to all who attended and participated in the lively Discord back channel, and to all you out there who keep the hacking flame alive. We couldn’t do it without you, and we look forward to a return to “normal” Supercon sometime soon.

The firmware wasn’t complete, though; there were jumps to places outside the code [Sprite] had and a large block looked corrupted. There’s another thing you can do with an executable file: run it. With

The firmware wasn’t complete, though; there were jumps to places outside the code [Sprite] had and a large block looked corrupted. There’s another thing you can do with an executable file: run it. With