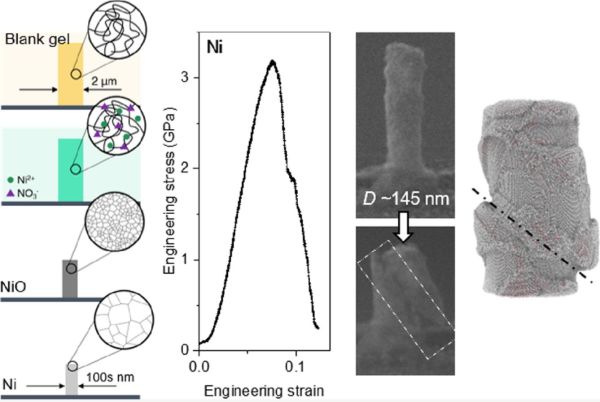

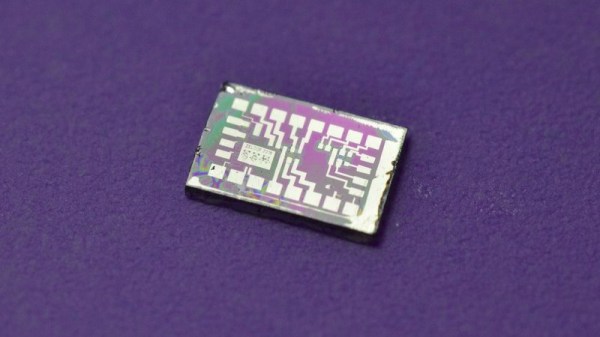

nanopillars. (Credit: Zhang et al., 2023)

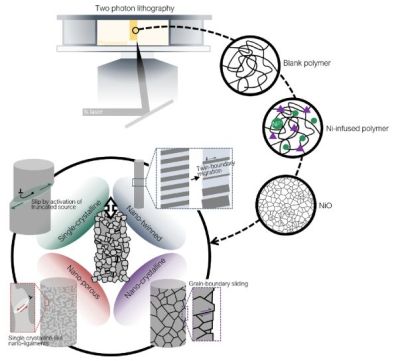

Manufacturing nano-sized features is rapidly becoming an essential part of new technologies and process, ranging from catalysts to photonics and nano-scale robotics. Creating these features at scale and in a reproducible manner is a challenge, with previous attempts using methods ranging from dealloying and focused ion beams to templated electrodeposition all coming with their own drawbacks. Here recent research by Whenxin Zhang and colleagues as published in Nano Letters demonstrates a method using additive manufacturing.

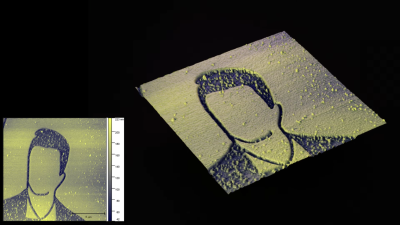

Specifically, nanopillars were printed in a hydrogel polymer with a laser-based lithography method called two-photon absorption which allows for a femtosecond laser to very precisely affect a small region within the targeted material with little impact on the surrounding area. This now solid and structured polymer hydrogel was then submerged into a Ni(NO3)2 solution to infuse it with nickel. After drying, the resulting structure had the polymer burned away in a furnace, leaving just the porous Ni nanopillars.

Subsequent testing showed that these nanopillars were more robust than similar structures created using other methods, presumably due to the less ordered internal physical structure of each pillar. Based on these results, it’s likely that the same approach could be used for other types of nano-sized structures.